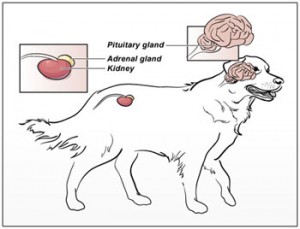

Picture an adrenal gland as a peanut M&M™. Cushing’s disease (or hyperadrenocorticism) is a problem with the chocolate coating, and it is much more common in dogs than in cats.

As part of this condition the adrenal glands overproduce certain hormones, particularly the body’s own steroid called cortisol. An elevated blood cortisol level is responsible for the major clinical signs observed by pet parents.

What causes Cushing’s disease?

There are four major ways by which Cushing’s disease can occur, and it is important to definitively determine a patient’s form of Cushing’s disease to ensure the most appropriate treatment.

ACTH-dependent (previously called pituitary-dependent): This is the most common form of Cushing’s disease, and is characterized by an over-production of a hormone called adrenocorticotropic hormone or ACTH. This hormone is produded by the pituitary gland in the brain and stimulates both adrenal glands to make cortisol. Approximately 85% of patients with Cushing’s disease have this form. Rarely (<10% of the time) the pituitary gland does more than produce an excess amount of ACTH – it actually increases in size; this is called a pituitary macroadenoma, and can be associated with neurologic deficits.

ACTH-independent (previously called pituitary-independent): Cushing’s disease may be the result of a benign (non-cancerous) or malignant (cancerous) mass of an adrenal gland. Currently the only way to determine if an adrenal mass is cancerous or not is via surgical removal. If the mass is benign, surgical resection is typically curative. If the mass is cancerous, additional treatment (such as chemotherapy) may be indicated. Some adrenal masses are not resectable. For these patients, treatment with a medication may be pursued; however without surgical removal, the nature of the mass will not be known.

Iatrogenic: Iatrogenic (meaning induced by medical treatment) Cushing’s disease results from excessive administration of a steroid like prednisone.

This may occur from oral, topical, and/or injectable medications prescribed by a veterinarian or self-administered by a parent without veterinary prescription.

Occult/Atypical: This form of Cushing’s disease is relatively controversial among board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialists. This manifestation of Cushing’s disease was discovered after veterinarians attempted to diagnose the disease in dogs with consistent clinical signs but for whom blood and urine tests were repeatedly negative. In other words, the dogs walked like a duck and quacked like a duck, but no test proved there was a duck! Affected patients do not have elevated blood cortisol levels, but rather appear to have elevations of various sex hormones (i.e.: estradiol, progesterone, 17-OH progesterone) produced by the adrenal glands that can induce similar clinical signs as cortisol.

What are the clinical signs of Cushing’s disease?

The most common clinical signs associated with Cushing’s disease are:

- Increased appetite

- Increased thirst

- Increased frequency of urination

- Increased panting

- Poor hair coat

(Image courtesy of Mark E. Peterson, DVM, DACVIM)

(Image courtesy of Mark E. Peterson, DVM, DACVIM)

- Weight gain

- Reduced activity level

Many of these dogs develop a “pot-bellied” appearance due to increased fat within the abdominal organs (most notably the liver), as well as stretching and weakening of the abdominal wall. Dogs with Cushing’s disease should not vomit, have diarrhea, or have a reduced appetite.

(Image courtesy of Mark E. Peterson, DVM, DACVIM)

(Image courtesy of Mark E. Peterson, DVM, DACVIM)

How is Cushing’s disease diagnosed?

A veterinarian’s decision to pursue diagnostic testing for Cushing’s disease should initially be based on a complete patient history and thorough physical examination that raises suspicion for the disease. A veterinarian will then perform some preliminary blood and urine tests, most notably a complete blood count (CBC), biochemical profile (CHEM) and urinalysis (UA).

(Image courtesy of Dr. T. Champney)

(Image courtesy of Dr. T. Champney)

The results are these preliminary tests in combination with appropriate clinical signs will help a veterinarian decide if further screening for Cushing’s disease is indicated. A complete diagnostic investigation for Cushing’s disease not only confirms the presence of the disease (screening diagnostics) but also determines whether the disease is caused by a pituitary or adrenal gland problem (localizing diagnostics).

Low suspicion for Cushing’s disease: If a veterinarian has a low suspicion of Cushing’s disease because a patient has an abnormal blood value but no clinical signs of the disease, a urine test called a urine cortisol:creatinine (UC:Cr) ratio is recommended.

The urine sample must be collected by a pet parent at home at least 72 hours after visiting a veterinarian.

This test has a high negative predictive value; this means if the test is normal, Cushing’s disease is highly unlikely. However if the result is abnormal, further testing is required to determine if a patient is living with the disease.

High suspicion for Cushing’s disease: If a veterinarian has a high index suspicion of Cushing’s disease based on a patient’s history, physical examination and initial laboratory test results, additional blood testing is indicated. One should note there is no test for Cushing’s disease that is accurate 100% of the time, and the two most commonly performed screening assays are the low-dose dexamethasone suppression test (LDDST) and the ACTH stimulation test (often called a “stim”). Patients suspected of living with occult/atypical Cushing’s disease will have a test called an adrenal sex hormone profile performed. Each screening test has its own benefits and limitations, and accordingly, a consultation with board-certified veterinary internal medicine speciailist can be invaluable to help decide which one is most appropriate.

Once a patient has been confirmed to be living with Cushing’s disease, one must then determine if the pituitary gland or an adrenal gland is the culprit. Common ways of differentiating ACTH-dependent from ACTH-independent Cushing’s disease include:

- A high-dose dexamethasone suppression test (HDDST)

- Combination of an abdominal ultrasound and endogenous ACTH level

An abdominal ultrasound examination with a board-certified veterinary radiologist or internal medicine specialist can be invaluable. This non-invasive test permits visualization of both adrenal glands and allows determination of their size and the presence of a mass. For patients in whom a pituitary macroadenoma is suspected, advanced imaging of the brain (i.e.: CT scan or MRI) is required. A consultation with a board-certified veterinary neurologist may also be quite beneficial.

What are the treatment options for Cushing’s disease?

Appropriate treatment of Cushing’s disease depends on whether it is ACTH-dependent, ACTH-independent, occult, atypical or iatrogenic in nature. Effective treatment absolutely requires a commitment by pet parents to administer any prescribed medication as directed and to meet all follow-up recommendations made by the attending veterinarian. Serial monitoring is required, and compliance of pet parents is essential for appropriate treatment.

ACTH-dependent: This most common form of Cushings’ disease is treated lifelong with a medication to help reduce the amount of cortisol made by the adrenal glands. The most common medications are mitotane (Lysodren®, o,p’-DDD) and trilostane (VETRORYL®). Each drug works differently but ultimately achieves the same goal – a reduction in cortisol production by the adrenal glands.

Board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialists have extensive experience managing Cushing’s disease patients with both of these medications, and consultation with one of them will likely be very helpful. With an adequate response to therapy, affected patients can live a high-quality of life for years. Previously used medications such as ketaconazole and L-deprenyl have fallen out of favor with veterinary internal medicine specialists because of their lack of efficacy and potential side effects.

For patients confirmed to be living with a pituitary macroadenoma, treatment is quite specialized. Surgery may be performed by board-certified veterinary surgeons at specific referral hospitals in the country; techniques have been developed to remove a pituitary adenoma (adenomectomy), to remove of a significant part of the pituitary mass (pituitary debulking) and to completely remove the pituitary gland (hypophysectomy). Stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) is a form of radiation therapy that focuses high-power energy on a small area of the body. Despite its name, radiosurgery is not a surgical procedure but rather is a form of treatment. Certain referral hospitals in the country are able to perform SRS, and treatment is performed under the direction of a board-certified veterinary radiation oncologist.

ACTH-indenpdent: If a patient with Cushing’s disease is living with a mass on one of the adrenal glands, surgery should ideally be performed to remove it. Surgical resection is currenlty the only way to determine if an adrenal mass is cancerous or benign. Removal of a benign mass is typically curative, and those with a cancerous adrenal mass may require further treatment (i.e.: chemotherapy). Unfortunately for some patients, surgery is not the best intervention, and for this population, treatment with trilostane may be helpful.

Iatrogenic: Treatment of this form of Cushing’s disease requires discontinuation of the steroid being administered; this must be done in a controlled manner to avoid other complications. Unfortunately steroid withdrawal usually results in a recurrence of the disease for which the steroid was originally prescribed.

Occult/Atypical: As mentioned previously, this form of the disease is relatively new, and thus the ideal treatment has not yet been determined. Commonly used medications are melatonin and HMR lignans, both of which are over-the-counter supplements that may help reduce the body’s production of certain sex hormones.

Nevertheless some patients with occult/atypical Cushing’s disease require treatment with a prescription medication like mitotane.

The take-away message about Cushing’s disease…

Cushing’s disease is a relatively common hormonal disorder in dogs and rarely in cats characterized by an excessive production of the body’s own steroid called cortisol by the adrenal glands. Affected patients typically drink and eat excessively, pant more, and urinate more frequently. Hair coat and body conformation changes are also quite common. Consultation with a board-certified veterinary internal medicine can be extremely helpful when planning a diagnostic investigation and/or formulating the most appropriate treatment plan for an affected pet.

To find a board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialist, please visit the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine.

To find a board-certified veterinary radiologist, please visit the American College of Veterinary Radiology.

To find a board-certified veterinary surgeon, please visit the American College of Veterinary Surgeons.

Wishing you wet-nosed kisses,

cgb