This week’s post is the second in a three-part series covering the topic of diabetes mellitus, and for this contribution I discuss this disease as it relates to dogs. In last week’s post, I reviewed diabetes in cats, and next week I will review insulin handling and how to perform at-home glucose monitoring in diabetic pets.

Diabetes mellitus – what causes it?

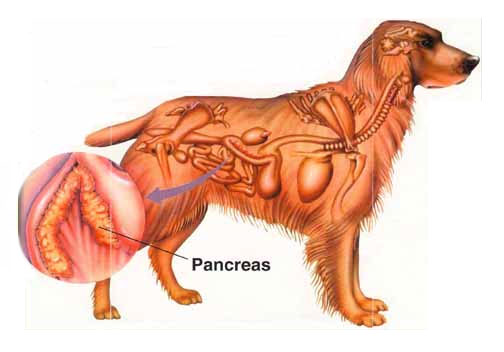

Glucose (also known as blood sugar) is required by every cell to function properly. A hormone called insulin secreted by the pancreas is required to transport glucose from the blood into cells. For dogs with diabetes mellitus, the pancreas simply can no longer produce enough insulin.

In dogs there is evidence the immune system slowly attacks the insulin producing cells of the pancreas (called beta cells found in the Islets of Langerhans). When enough beta cells are affected, diabetes mellitus occurs.

Other causes of diabetes mellitus in dogs include:

- Genetic predisposition

- Chronic pancreatitis

- Medications (i.e.: megestrol acetate, glucocorticoids)

Certain breeds are genetically predisposed to developing diabetes mellitus, particularly:

- German shepherds

- Schnauzers (all sizes)

- Beagles

- Poodles (all sizes)

- Golden retrievers

- Keeshonds

Diabetes mellitus – what are the clinical signs?

Females are more often affected than male dogs, and canines that develop this disease are commonly middle aged (i.e.: 6-9 years of age). Juvenile diabetes is relatively uncommon in dogs, but Golden Retrievers and Keeshonds are over-represented for this form of diabetes.

The major clinical signs of diabetes mellitus in dogs are very similar to those observed in cats:

- Increased thirst (polydipsia)

- Increased volume & frequency of urination (polyuria)

- Weight loss in the face of an increased appetite

Additionally dogs often form cataracts, a change to the lenses of the eyes that causes (often acute/sudden) blindness.

Diabetes mellitus – how is it diagnosed?

Just as in cats, the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus in dogs is relatively straightforward. The presence of elevated blood glucose (called hyperglycemia) and extra glucose in the urine (called glucosuria) in patients who are losing weight despite a voracious appetite, drinking excessively and/or urinating more frequently is diagnostic for diabetes mellitus.

Stress can cause excess blood sugar and urine glucose, and understandably this can be confusing at times. For these patients, a special blood test called a fructosamine level can be uniquely helpful. Remember from our discussion about diabetes in cats that fructosamine is a glycated protein (forms when glucose combines with protein) similar to hemoglobin A1c measured in human diabetic patients. A fructosamine level reflects an average blood glucose level over the previous 2-3 weeks; thus if this level is also elevated, diabetes mellitus can be distinguished from a one-time, stress-induced glucose elevation. Ultimately a consultation with a board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialist can be instrumental in making an accurate diagnosis.

Diabetes mellitus – how is it treated?

There are four main goals are treatment of diabetes mellitus in dogs:

- Eliminate the clinical signs of disease

- Prevent the formation of cataracts

- Prevent low blood sugar

- Treat and prevent concurrent diseases

Dogs almost always require lifelong therapy with insulin. Their disease is termed insulin-dependent, and in my many ways is essentially identical to Type I diabetes in people. Insulin from dogs is not yet commercially available, but porcine (meaning from pigs) insulin is, and canine and porcine insulin are molecularly identical. For this reason, the initial insulin of choice for diabetic dogs is Vetsulin, a porcine-based insulin.

There are several other insulins that are available to use in dogs as well, including Humulin/Novolin N, glargine and detemir. These insulins are of human origin. When dogs are given human-type insulins, there is the possibility they will subsequently make proteins called antibodies that could theoretically make diabetic control more challenging. Thankfully, to date, the formation of anti-insulin antibodies in dogs has not led to poor glucose control in dogs treated with human insulin.

Diets that have moderate levels of fiber and low fat are preferred for dogs with diabetes mellitus. Common prescription examples include:

- Hill’s Prescription Diet w/d

- Royal Canin Diabetic

- Purina DCO

Fiber slows the transit of glucose from the intestines to the bloodstream, resulting in a more gradual rise of blood sugar levels. A pet’s primary care veterinarian should determine the number of calories a dog requires per day, and dogs should be fed two equally-portioned meals every 12 hours prior to insulin therapy. The food source eaten by diabetic dogs should be constant, as diabetic control is exceedingly difficult if the ingredient source varies. Overweight and obese pets should be enrolled in a weight loss program, as excess fat tissue reduces the efficacy of insulin therapy. Consultation with a board-certified veterinary nutrition specialist can be quite helpful when picking the best food for diabetic dogs.

Dogs with diabetes mellitus have no specific exercise requirements. However physical activity can change a patient’s insulin requirements, and for this reason, a diabetic dog’s exercise regime should be as regular and consistent as possible. “Weekend warrior” activity (i.e: very active on the weekends but relatively sedentary on the weekdays) should be avoided.

The take-away message about diabetes mellitus in dogs…

The number one cause of death in diabetic dogs is not the disease itself. Rather it is families electing humane euthanasia because of frustrations with disease management. Pet parents must be comfortable with treating diabetic dogs, as any insecurity can lead to treatment failure. Pet parents need to know about many facets of this disease, particularly:

- How to give insulin injections

- How to store and mix insulin

- What and when to feed their dog

- How to recognize and treat low blood sugar

If a diabetic dog parent doesn’t know this information, s/he should immediately request a consultation with her/his pet’s primary care doctor to review this information. If this isn’t possible and/or if more knowledge is desired, a consultation with a board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialist is recommended.

To find a board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialist, please visit the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine.

To find a board-certified veterinary nutritional specialist, please visit the American College of Veterinary Nutrition.

Wishing you wet-nosed kisses,

cgb