Hepatic encephalopathy is a multifactorial neurologic syndrome that occurs when liver dysfunction causes systemic biochemical alterations that disrupt brain metabolism. The most frequently reported cause of hepatic encephalopathy, sometimes referred to as a hepatic coma or HE, in dogs is portosystemic vascular anomalies (aka: liver shunts). There are three types of hepatic encephalopathy:

- Type A – associated with acute liver failure

- Type B – associated with a liver shunt without intrinsic liver failure

- Type C – associated with marked liver disease and high pressure within major liver blood vessels (aka: portal hypertension)

What do pets with hepatic encephalopathy look like?

There is no breed, sex or age predilection for hepatic encephalopathy; however there are predilections for specific diseases (i.e.: portosystemic vascular anomalies / liver shunts) commonly associated with this syndrome. Patients with congenital liver shunts typically show clinical signs within 12 months of life, but shunts are occasionally diagnosed in older patients. Extra-hepatic (outside the liver) shunts most commonly occur in small and toy breed dogs (i.e.: Yorkshire terriers, Miniature Schnauzers, Maltese, Havanese, Pugs) and cats.

Intra-hepatic (inside the liver) shunts are typically documented in large breed dogs (i.e.: Labrador Retrievers, Irish Wolfhounds.

Patients with acquired liver diseases commonly manifest clinical signs when greater than one year of age

What are the risk factors for hepatic encephalopathy?

Several risk factors have been identified that can contribute to the development of this syndrome, including:

- Excessive protein ingestion

- Gastrointestinal hemorrhage

- Constipation

- Low potassium

- Low blood sugar

- Low sodium

- Kidney disease

- Infection

- Certain medications (i.e.: ketoconazole, chloramphenicol, cimetidine, barbiturates)

Patients with extra-hepatic liver shunts are often the runt of their litters, have retained deciduous (baby) teeth, and/or open fontantelles (soft spot on top of the head).

There is also a higher prevalence of cryptorchidism (absence of one or both testicles in the scrotum) documented in affected males. Families may report their pet drinks a lot, urinates large volumes frequently and/or was difficult to house-train.

What are the clinical signs of hepatic encephalopathy?

Clinical signs are commonly divided into four stages. Common clinical signs of Stage I are confusion, decreased appetite, dull mentation or irritability; however patients can actually appear quite normal to both veterinarians and pet parents. Stage II patients frequently manifest a dull mentation, blindness, excessive drooling, lethargy, stumbling, and personality changes. Stage III patients are often stuporous and confused, can have seizure activity and may be aggressive; some cats will developed copper-colored irises.

Lastly patients living with Stage IV disease are recumbent and may slip into a coma that can rapidly lead to death if immediate medical intervention is not provided. Interestingly patients commonly fluctuate episodically between stages.

What tests are needed to diagnose hepatic encephalopathy?

Veterinarians will initially need to perform some non-invasive blood and urine tests, including:

- Complete blood count

- Serum biochemical profile

- Urinalysis

- Serum bile acids

- Blood ammonia level

Diagnostic imaging is frequently needed, most commonly abdominal radiography (x-rays) or abdominal ultrasonography. Advanced imaging studies, including computed tomography (CT scan) and portography (injection of special dye into the system of blood vessels that travel to the liver), might be needed.

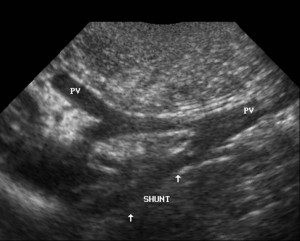

Ultrasound image of a liver shunt (portoazygous) in a dog. Photo courtesy of Susquehanna Veterinary Imaging, LLC

Consultation with a board-certified veterinary radiologist or board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialist can be invaluable when selecting the most beneficial imaging study. Ultimately sampling the liver (i.e.: biopsy) may be needed to confirm inflammatory, infectious and/or cancerous processes.

How is hepatic encephalopathy treated?

The three goals of the management of hepatic encephalopathy are:

- To reduce the incidence of predisposing factors

- To alleviate neurologic signs

- To determine the primary underlying liver disease

Veterinarians often prescribe medications that help modify bacteria in the colon and/or help the body get rid of these bacteria. Patients should be fed as much protein as they can tolerate, and your veterinarian will counsel you regarding your pet’s specific nutrition requirements; excessive protein intake should be avoided. Consultation with a board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialist or board-certified veterinary nutrition specialist can be invaluable. Drugs metabolized by the liver should be used cautiously, and electrolyte (i.e.: sodium, potassium) derangements must be corrected. In patients with extra-hepatic shunts, surgery to close the shunt may be curative.

The take-away message about hepatic encephalopathy

Hepatic encephalopathy is a complicated process that arises secondary to a myriad of factors, and the clinical and biochemical abnormalities associated with this syndrome cannot be sufficiently explained by any single liver or brain metabolic defect. Thorough investigation and comprehensive therapies are of paramount importance, and consultation with a board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialist can be uniquely helpful in maximizing the likelihood of a meaningful recovery.

To find a board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialist, please visit the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine.

To find a board-certified veterinary emergency and critical care specialist, please visit the American College of Veterinary Emergency and Critical Care.

To find a board-certified veterinary radiologist, please visit the American College of Veterinary Radiology.

To find a board-certified veterinary nutrition specialist, please visit the American College of Veterinary Nutrition.

Wishing you wet-nosed kisses,

cgb