In the northern hemisphere we are entering the Summer season. Warmer months bring an increased risk for various health concerns for our dogs, including infectious diseases. This week I share information about a potentially lethal bacterial infection called leptospirosis. I believe you will find the topic especially relevant, and therefore, I hope you will share it with other canine caretakers. Happy reading!

Leptospirosis – What is it?

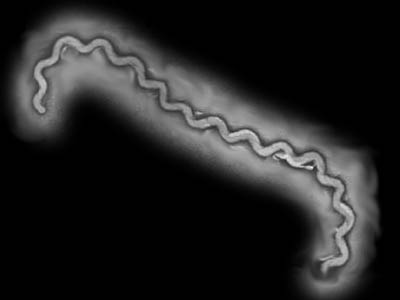

Leptospirosis is a potentially fatal disease caused by the bacterium, Leptospira interrogates. This bacterium not only causes disease in dogs, but also in people too. In fact, one’s own dog can infect you! Leptospira interrogans comes in dozens of strains called serovars. Only a few of them cause disease in our canine companions. The serovars of which we are most concerned are:

- L. grippotyphosa

- L. pomona

- L. canicola

- L. icterohemorrhagiae

In nature, serovars persist in various wildlife that serve as reservoir hosts. These animals have subclinical infections, and therefore, they shed the bacterium in their urine. Common reservoir hosts are:

- L. grippotyphosa – raccoon, skunk, opossum, small rodents, and squirrels

- L. pomona – skunk, raccoon, cow, pig, and deer

- L. canicola – dog

- L. icterohemorrhagiae – rat, pig

Although infection may occur anywhere, leptospirosis is more commonly documented in warm climates with meaningful annual precipitation. Contaminated water and/or the urine of infected animals can readily subsequently infect dogs; our canine friends encounter such environments in a variety of ways:

- Exposure to or drinking from various bodies of water (including puddles)

- Exposure to wild and/or farm animals

- Contact with rodents or other dogs

- Roaming on rural properties with exposure to wildlife, farm animals, and/or water sources

Bite wounds, reproductive secretions, and even ingestion of infected tissues may also result in infection.

Leptospirosis – What does infection look like?

Leptospira serovars flourish in rural, suburban, and urban areas. Veterinarians most commonly diagnose infections between July and December each year. With ever-growing populations of raccoons, skunks, and various rodents, the potential for exposure and infection is ubiquitous.

The clinical signs of leptospirosis are highly variable and non-specific. Certain serovars cause different types of illness. Depending on the implicated serovar(s), infected dogs may develop acute kidney injury (AKI) and/or liver damage – 90% and 10-20%, respectively. Common clinical signs are:

- Lethargy & depression

- Reduced (or loss of) appetite

- Nausea and/or vomiting

- Increased thirst

- Increased frequency of urination

- Icterus/jaundice (yellow appearance to skin and/or sclera (“whites of the eyes”)

- Fever

- Abdominal pain

- Muscle pain

- Diarrhea

- Joint pain / stiffness

- Inability to get pregnant

- Blood clotting abnormalities

- Uveitis (Inflammation inside the eyes)

Leptospirosis – How is infection diagnosis?

The diagnosis of leptospirosis is not straightforward, so making an accurate diagnosis is challenging. Dogs properly vaccinated against leptospirosis can test positive via some of the common screening tests. Partnering with a board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialist can be uniquely helpful. Veterinarians perform various non-invasive blood and urine tests, as well as diagnostic imaging studies (i.e.: abdominal ultrasonography). Each test looks for a unique piece of information to help your pet’s medical team make a definitive diagnosis. Unquestionably, early diagnosis and therapy are essential of paramount importance!

Leptospirosis – How is it treated?

The type and level of intervention required for dogs infected with leptospirosis depends on a variety of factors, including the involved serovar(s), time to diagnosis, and the presence of kidney and/or liver injury. Some infected dogs may be treated on an out-patient basis with antibiotic therapy and non-specific supportive care. The initial antibiotics of choice are doxycycline and penicillin (or one of its derivatives) since they eradicate the infective organism from the blood within 24 hours. Doxycycline is commonly administered for three weeks to prevent a state where the patient becomes a chronic carrier and shedder of the bacterium.

Dogs with kidney and/or liver damage typically require aggressive around-the-clock supportive care in a specialty referral hospital. Intravenous delivery of fluids and various medications, including antibiotics, can be life-saving. Partnering with a board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialist and/or a board-certified veterinary emergency & critical care specialist can be instrumental for maximizing a positive outcome. With early recognition and appropriate therapies, the survival rate for dogs with AKI is approximately 80%.

Leptospirosis – What about me?

Infected dogs can shed Leptospira in their urine. When infected urine comes into contact with mucosal surfaces (i.e.: gums, eyes, nose, etc.) or a skin defect of a person, human infection is possible. Pet parents of a dog known (or suspected) to be living with leptospirosis should immediately contact their personal physicians to determine if any testing and/or therapeutic intervention is indicated. Anyone who handles and works with infected dogs should exercise proper hand-washing techniques. Children, the elderly, and those with compromised immune systems should not handle dogs with leptospirosis.

Leptospirosis – Can it be prevented?

A vaccination is available against the four most common serovars of Leptospira interrogans. Vaccination reduces the severity of disease. It does not prevent infection or prevent infected dogs from becoming carriers of the disease. Pet parents should speak with their primary care veterinarians to determine if the leptospirosis vaccination is recommended for dogs in their geographic area.

The take-away message about leptospirosis in dogs…

Leptospirosis is a serious bacterial infection in dogs with major public health implications. People may be infected by contact with affected canines. Early diagnosis and treatment are fundamental. Partnering with board-certified veterinary specialists in internal medicine and emergency & critical care can be wholly beneficial to augment the likelihood of a meaningful recovery.

To find a board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialist, please visit the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine.

To find a board-certified veterinary emergency and critical care specialist, please visit the American College of Veterinary Emergency & Critical Care.

Wishing you wet-nosed kisses,

cgb