The heart is unquestionably a vital organ. Unfortunately, sometimes it doesn’t develop properly in utero, and these congenital defects can range from minor and inconsequential to life threatening. This week I share information about a relatively common congenital heart defect called subaortic stenosis. Please consider sharing it with other pet parents. Happy reading!

Subaortic Stenosis – What is it?

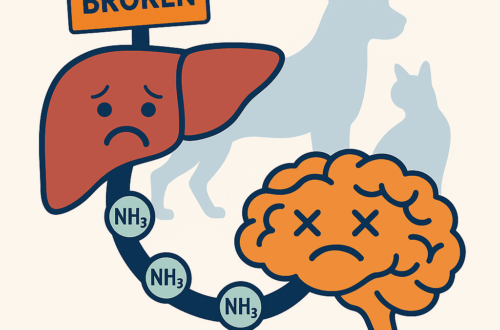

To understand subaortic stenosis, one must have a basic understanding of basic heart anatomy. The heart has two sides – a left side and a right one. The right side receives deoxygenated blood from the body and then pumps it to the lungs to be oxygenated. The left side receives oxygenated blood from the lungs and then pumps it to the body to be used by important organs. Before leaving the left side of the heart, blood must pass through a special gate called the aortic valve. In patients with subaortic stenosis, the area below the aortic valve (subaortic) is inappropriately narrowed (stenosis). The stenosis is caused by a ring of fibrous tissue that forms in this region.

Depending on how much fibrous tissue develops, the stenosis may be mild, moderate, or severe. With the abnormal narrowing, the heart has to work much harder to pump blood out to the body. As a result, the heart muscle becomes thickened (hypertrophied). Thickened heart muscle is more difficult oxygenate, and abnormal and potentially lethal heart rhythms can develop when heart muscle doesn’t get enough oxygen.

Subaortic Stenosis – What does it look like?

Any dog can develop subaortic stenosis, but this condition is quite rare in cats. Furthermore, large breed dogs are over-represented; furthermore, for some subaortic stenosis is an inherited problem, including:

- English bulldogs

- Boxers

- German shepherds

- Golden retrievers

- Great Danes

- Mastiffs

- Newfoundlands

- Rottweilers

- Samoyeds

Patients with subaortic stenosis have a variety of clinical signs depending on the degree of stenosis. Common signs are:

- Weakness

- Difficulty breathing (called dyspnea)

- Fainting (called syncope)

- Exercise intolerance

- Sudden death

Veterinarians will perform a complete physical examination. A heart murmur is typically detected when affected dogs are puppies, but occasionally is heard after one year of age. Occasionally, dogs will have abnormal lungs sounds due to left-sided heart failure.

Subaortic Stenosis – How is it diagnosed?

As mentioned earlier, veterinarians will perform a thorough physical examination, including listening extensively to the heart to hear a murmur and/or an abnormal heart rhythm. If this condition is suspected based on breed, clinical signs, and physical examination findings, veterinarians will recommend additional testing, particularly:

- Chest radiographs (x-rays)

- Electrocardiogram (ECG, EKG)

- Echocardiogram (heart ultrasound)

- Fluoroscopy – see video below

Pet parents will likely find it quite invaluable to partner with a board-certified veterinary cardiologist to ensure a proper diagnosis is made.

Subaortic Stenosis – How is it treated?

There is no cure for subaortic stenosis. Patients with a mild form of this condition do not require any specific treatment. However, if the condition worsens and in severely affected dogs, intervention is required. Initially, a type of medication called a beta-blocker is given to help reduce the work of the heart, to control the heart rate, and to reduce the incidence of abnormal heart rhythms. Surgical and minimally invasive procedures may also be recommended, including cutting and non-cutting balloon catheterization (see video below).

Dogs with subaortic stenosis should not be bred. Pet parents are strongly recommended to consult with a board-certified veterinary cardiologist to determine the best treatment modality.

The take-away message about subaortic stenosis in dogs & cats…

Subaortic stenosis is a congenital heart condition that ranges in severity. Diagnosis is based on a combination of clinical signs and non-invasive diagnostic imaging studies. Mildly affected patients may only require serial monitoring while more seriously affected pets can benefit from medication and/or minimally invasive balloon catheterization.

To find a board-certified veterinary cardiologist, please visit the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine.

Wishing you wet-nosed kisses,

CriticalCareDVM