It’s vaccine season. In a previous post, I reviewed the most recent recommendations for feline immunizations. Cat parents are getting emails and postcards from their primary care veterinarians reminding to schedule preventative healthcare visits. One of the most common vaccines is abbreviated FVRCP, an acronym for feline viral rhinotracheitis, calici virus, and panleukopenia (aka distemper). This week we’ll discuss feline viral rhinotracheitis caused by feline herpesvirus-1 (FHV-1). Herpesvirus is the most common upper respiratory tract infections in cats, so I felt it was important to dedicate time to sharing information about it. Happy reading!

Herpesvirus – What is it?

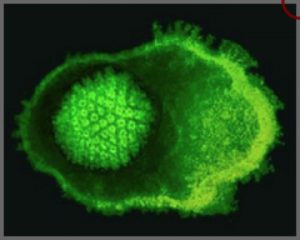

Feline herpesvirus-1 is a double-stranded deoxynucleic acid (DNA) enveloped alpha herpesvirus. The virus is prevalent in the feline population, particularly in shelters and catteries. Upon entry into the respiratory tract, the virus replicates in the cellular lining (called epithelial mucosa) of many different structures, including the cornea, conjunctiva, tonsils, nasal septum and turbinates, and nasopharynx. The mucosa is damaged during viral replication, resulting in erosions and ulcers in infected tissues. The virus can permanently damage the nasal turbinates, setting a cat up for chronic upper respiratory signs. Infected cats may also develop secondary bacterial infections in their sinuses and/or lungs.

Electron micrograph of herpesvirus. Image courtesy of Fred Murphy.

Feline herpesvirus-1 is rapidly shed in secretions of the eyes, nose, and mouth, sometimes in as little as 24 hours after infection. Cats are infected most commonly when they come into direct contact with infected cats or with objects with the virus on it (called a fomite). Transmission through respiratory droplets (called aerosol transmission) is much less common because those droplets don’t travel more than five feet given a cat’s lung capacity.

Most cats with feline herpesvirus-1 infection are never cured. Kittens and more than three in four cats become latently infected. The virus lays dormant in specific parts of the nervous system, particularly the trigeminal ganglion, optic nerve & chiasm, and the olfactory bulb. Reactivation of the virus most commonly occurs due to a stressful event, including:

- Introduction of a new pet into a residence

- Overcrowding in shelters / catteries

- Anesthesia & surgery

- Moving

- Pregnancy & lactation

- Treatment with immune system-suppressing drugs

- Concurrent health condition

Upon reactivation, cats shed the virus in various oral, nasal, and ocular secretions for one week with clinical signs seen for upon to two weeks.

Herpesvirus – What does it look like?

Given feline herpesvirus-1 is the most common cause of upper respiratory tract infection in cats, the clinical signs seen in cats are referable to the eyes and nose, and include:

- Sneezing

- Nasal discharge

- Ocular discharge

- Eye changes – reddening, symblepharon (adherence of conjunctiva and/or eyelid to the cornea), corneal ulcerations, corneal sequestra, anterior uveitis (inflammation in the anterior chamber of the eye)

- Corneal ulcers

- Lethargy

- Reduced (or loss of) appetite

- Coughing

Kitten with feline herpesvirus-1 infection. Note the ocular and nasal discharge characteristic of this infection.

There is no breed or sex predilection, but pediatric and immunocompromised patients are over-represented for having feline herpesvirus-1 infection. Brachycephalic (i.e.: short-nosed breeds) breeds seem to develop chronic complications from infection – rhinitis and sinusitis – more commonly.

Herpesvirus – How is it diagnosed?

A veterinarian will recommend definitive diagnostic testing in cats with a history and clinical signs consistent with feline herpesvirus-1 infection. Tests like polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay and virus isolation are most frequently used to reach a definitive diagnosis.

Herpesvirus – How is it treated?

Viruses are more challenging to treat with medication than bacterial infections. Some antiviral medications – both systemic and ophthalmic – have shown promise in helping reduce the severity of clinical signs, specifically famciclovir and idoxuridine. A supplement called L-lysine may help slow the replication of the virus, but research findings have not been conclusive.

Many patients with feline herpesvirus-1 do not need an antibiotic. Indeed, it is my opinion antibiotics are inappropriately prescribed for many patients with this viral infection. Why? Veterinarians feel compelled to do something, and pet parents often insist their cats are prescribed an antibiotic even when such treatment isn’t indicated. Patients with feline herpesvirus-1 infection should only receive antibiotic therapy if they have evidence of secondary bacterial infection, such as colorful (i.e.: yellow/green) nasal and/or ocular discharge.

Some patients required temporary fluid therapy and nutritional support because they can’t or are unwilling to eat. Nasal decongestants and antihistamines may be helpful for some cats, but benefits are not consistent. Most cats with acute clinical signs recover within supportive care within two weeks. One must remember many of these cats become chronic carriers of the virus and may develop clinical signs in the future.

Herpesvirus – Can it be prevented?

Appropriate vaccination can help reduce the incidence of infection. Concurrent illnesses can predispose to recurrent clinical signs in chronically infected cats, and thus preventative healthcare with primary care veterinarians is essential to keep our feline friends happy and healthy. Acutely infected cats are highly contagious and should be isolated from other cats. Caregivers should wear personal protective equipment (i.e.: gloves, gowns, etc.) to prevent accidental transmission.

The take-away message about herpesvirus infection in cats…

Feline herpesvirus-1 is the most common cause of upper respiratory infections in cats. Affected cats typically have nasal and ocular signs. Within supportive care, the majority of cats recover from their acute clinical signs within two weeks. Unfortunately, many cats become chronic carriers of the virus, putting them at risk for disease recurrence later in life.

For more general information on sneezing, you may find this article written by my colleague, Dr. Justine Lee, a board-certified veterinary specialist in emergency/critical care and toxicology.

To find a board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialist, please visit the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine.

Wishing you wet-nosed kisses,

CriticalCareDVM