Ingested food is broken down in the intestinal tract, and subsequently nutrients are absorbed into the bloodstream that travels to the liver (called the portal blood supply). The liver is the vital organ tasked with using these nutrients to store sugar and produce protein, as well as clean the blood of metabolic waste products. A liver shunt is an abnormal blood vessel that transports blood around the liver rather than through it, and thus this organ is not able to perform its vital tasks. Other terms used for a liver shunt include portosystemic shunt (PSS) and portosystemic vascular anomaly (PSVA). There are two general types of liver shunts:

- Congenital – the result of a birth defect

- Acquired – the result of severe liver disease that causes pressure changes in liver blood vessels

All dog fetuses have a large shunt called the ductus venosus that carries blood through the fetal liver to the heart. Proper liver function is not required for fetuses because the mother’s liver performs all of the necessary vital functions discussed earlier in this post. A congenital portosystemic shunt develops if:

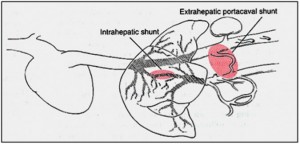

- The ductus venosus does not close at birth – this is called an intra-hepatic (formed inside the liver tissue) congenital portosystemic shunt

- A blood vessel outside the liver develops and remains open after the ductus venosus closes – this is called an extra-hepatic (formed outside the liver tissue) congenital portosystemic shunt

Which dogs get liver shunts?

Any dog can develop an acquired shunt(s) from liver disease. Similarly any dog can be born with a congenital shunt, but some breeds are over-represented for this birth defect. Small and toy breed dogs typically have extra-hepatic liver shunts, while large breed dogs more often have intra-hepatic ones. Yorkshire terriers are at more than 35 times the risk of developing a liver shunt compared to all breeds combined in the United States.

Other dogs in which extra-hepatic congenital portosystemic shunts are common are:

- Miniature Schnauzers

- Maltese

- Dachshunds

- Cocker spaniels

- Jack Russell terriers

- Lhasa apsos

- Cairn terriers

- Poodles

- Shih Tzus

Several breeds seem to be over-represented for having intra-hepatic liver shunts, including:

- Labrador retrievers

- Irish Wolfhounds

- Australian shepherds

- Australian cattle dogs

- Old English sheepdogs

- Samoyeds

Liver shunts are hereditary in Yorkshire terriers, Irish Wolfhounds, Cocker spaniels, and Maltese, and are suspected to be hereditary is several other breeds. Dogs with liver shunts should be castrated or spayed, and the parents of the affected animal should also not be bred.

Liver shunt clinical signs…

Dogs living with congenital liver shunts frequently develop clinical signs within 12 months of age, including:

- Poor growth and development –affected dogs are often the runt of their litters

- Quiet demeanor – families frequently note affects dogs were the calm ones in their respective litters

- Behavioral changes (i.e.: disorientation, head-pressing, staring into space, circling)

- Increased thirst and frequency of urination – may be from liver dysfunction or the formation of kidney and/or urinary bladder infections/stones

- Vomiting

- Difficulty house-training

- Neurologic changes (i.e.: unresponsiveness, blindness, seizures)

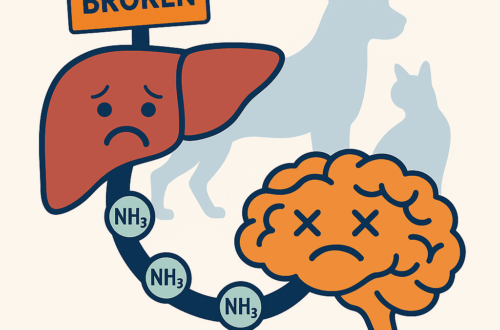

The neurologic and behavioral changes are the result of the accumulation of toxins and metabolic waste products in the bloodstream. Cumulatively these chemicals cause a syndrome called hepatic encephalopathy. To learn more about this syndrome, click here.

Liver shunt diagnosis…

One of the most important diagnostic tests for any pet with a health concern is providing your pet’s veterinarian with an accurate and thorough history. Does your dog drink a lot of water? Has it been difficult to house-train him/her? What information can you provide about your dog’s littermates? Have you observed any behavioral changes?

Your dog’s veterinarian will perform a complete physical examination, and will develop an appropriate diagnostic plan. The most common initial assays are non-invasive blood and urine tests called a complete blood count (CBC), serum biochemical profile (CHEM), and urinalysis (UA). If your pet’s history, physical examination and/or these preliminary blood/urine tests raise concerns about a liver shunt, further investigation will be recommended; possible additional tests include:

Bile acids: Bile acids are made by the liver and subsequently stored in the gallbladder. When a dog eats a meal, the bile acids are expelled from the gallbladder into the small intestines to help digest fat before they are reabsorbed and stored until the next meal. Bile acid levels are elevated in patients with liver shunts because the liver is not able to remove them from the blood for storage in the gallbladder.

Abdominal ultrasonography: An experienced ultrasonographer (either a board-certified veterinary radiologist or internal medicine specialist) may be able to visualize a liver shunt using a special sonographic technique that detects blood flow (called Doppler flow). However shunts can be easily missed, and thus if ultrasonography does not identify a liver shunt, this doesn’t mean a shunt has been 100% ruled out.

Scintigraphy: This is a special type of imaging test in which a medical-grade radioactive material is placed into the colon via an enema; the dog is subsequently scanned with a special camera. This test is safe and quick, but does require sedation and at least one night of hospitalization. Other limitations of this test include:

- Requirement of a specialized facility approved to store and administer medical-grade radioactive material

- Inability to differentiate extra- from intra-hepatic shunts

- Inability to determine if a shunt is acquired or congenital

- Inability to determine how many shunts are present

Computed tomography with angiography: This is a medical imaging technique that uses a CT scan and a special contrast agent/dye that is injected into a vein (called angiography). The contrast material travels throughout the circulatory system, including through a liver shunt, and multiple images are captured with the CT scan. This procedure is quite helpful, providing both diagnostic information and images that are helpful for planning surgical intervention. This is a specialized procedure that requires a brief period of anesthesia, and is frequently only available at veterinary specialty hospitals.

Portography: This is a radiograph (x-ray) taken of the blood vessels traveling to the liver after they are injected with a special contrast agent. This imaging test is most commonly performed via an injection directly into a blood vessel in the abdominal cavity, through a special catheter in a vein in the neck, or through an injection into the spleen. This procedure should be performed under the guidance of a board-certified veterinary surgeon, internal medicine specialist and/or radiologist, and does require sedation/anesthesia.

Liver shunt treatment…

Dogs with liver shunts initially receive various medications and a special diet to help treat clinical signs associated with hepatic encephalopathy. Consultation with a board-certified internal medicine specialist will likely be helpful in developing the most appropriate treatment plan for an affected pet. Most patients improve very quickly, and approximately 33% can live a high-quality life for a reasonably long period of time. Unfortunately more than 50% of dogs who only receive medical therapies are euthanized within 1 year of diagnosis due to uncontrollable neurologic signs.

Surgery offers the best potential chance for a cure for patients living with an extra-hepatic liver shunt. Multiple techniques are available to close an extra-hepatic shunt, including:

- Ameroid constrictor placement (most common)

- Cellophane banding

- Complete ligation/closure

Consultation with a board-certified veterinary surgeon is strongly recommended to determine the most appropriate surgical technique for addressing an extra-hepatic liver shunt. Intra-hepatic shunts historically have also been treated surgically, but this type of procedure is more invasive than that required for correcting extra-hepatic shunts. More recently the use of interventional radiology to place special coils inside an intra-hepatic shunt (called transvenous coil embolization) has been advocated, and is available at several veterinary specialty centers in the country. Click here to see a video this procedure.

After surgery, patients require hospitalization and around-the-clock monitoring for a few days. They are at-risk for developing low blood sugar post-operatively, and must be examined serially to assess their comfort level. A small percentage of patients will have post-operative seizures that require intervention. Rarely patients develop complications (i.e.: portal hypertension) that can be life threatening.

Long-term care after liver shunt surgery…

More than 95% of patients with extra-hepatic liver shunts that are surgically corrected with ameroid constrictors survive, and the vast majority are clinically normal within 1-2 months of surgery. Special diet and medical therapies for hepatic encephalopathy can frequently be weaned over 2-8 weeks, and liver function dramatically improves (and possibly normalizes) within 6 months of surgery. While 85% of patients treated with an ameroid constrictor clinically do very well, roughly 15% have residual clinical signs. This is likely due to the presence of minute blood vessels within the liver tissue; these patients will require medical therapy and a special diet for life.

The take-away message about liver shunts…

Liver shunts are complex anatomical abnormalities common in many breeds of dogs. Special diagnostic tests are needed to definitively diagnose this condition, and consultation with a board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialist can be helpful. Ultimately surgery affords patients the best opportunity to lead the highest possible quality of life for as long as possible, and thus consultation with a board-certified veterinary surgeon is strongly recommended once clinical signs of hepatic encephalopathy have been appropriately controlled.

To find a board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialist, please visit the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine.

To find a board-certified veterinary emergency and critical care specialist, please visit the American College of Veterinary Emergency and Critical Care.

To find a board-certified veterinary surgeon, please visit the American College of Veterinary Surgeons.

To find a board-certified veterinary radiologist, please visit the American College of Veterinary Radiology.

Wishing you wet-nosed kisses,

cgb