Red blood cell (RBC) transfusions supply critical oxygen-carrying cells to the body. Prior to the development of veterinary blood banking techniques, the major form of RBC transfusion was on-site collection of fresh whole blood (FWB) with subsequent administration within hours of collection. Today, however, the use of stored whole blood (WB) and packed red blood cells (pRBC) is much more common. Patients who may benefit from RBC transfusion(s) include:

- Patients who are bleeding

- Patients in whom RBCs are rupturing – this process (called hemolysis) may be triggered by infectious diseases, toxins, and/or the immune system

- Patients who do not have functional bone marrow, and thus can’t make new RBCs

The decision to provide a red blood cell transfusion to a patient is based on multiple factors, and is not based solely on a single measurement of red blood cell concentration. Veterinarians should take into account a patient’s age, breed, severity and duration of a patient’s low RBC count (called anemia), and underlying disease process when deciding whether or not to provide a red blood cell transfusion to a patient.

Red blood cell types – do dogs and cats have their own?

Most people are familiar with the human blood group, ABO; within this group are four principal blood types: A, B, AB, and O. Similarly dogs and cats have their own blood groups and types. These blood groups are determined by the presence (or absence) of certain molecules (antigens), typically proteins and carbohydrates/sugars, on the surface of red blood cells.

Currently there are more than a dozen dog blood groups and several possible dog blood types. However only one blood group, called dog erythrocyte antigen (DEA) 1 has meaningful clinical importance. Approximately 60% of dogs in the United States are DEA 1-positive.

There is only one feline blood group that has three possible blood types – A, B, and AB. Approximately 75-95% of cats have Type A blood, while 2-25% have Type B blood. Type AB blood is exceedingly rare (<1% of cats).

| Table #1: Incidence of feline blood types by USA geographic region(Wamsley, et al, 2012 CVMA Proceedings) | ||||

Region | # of Cats | %A | %B | %AB |

Northeast | 1450 | 99.7% | 0.3% | 0 |

North central | 506 | 99.4% | 0.4 | 0.2 |

Southeast | 534 | 98.5% | 1.5% | 0 |

Southwest | 483 | 97.5% | 2.5% | 0 |

| West coast | 812 | 94.8% | 4.7% | 0.5% |

| Table #2: Frequency of Type B blood in USA purebred cats(Wamsley, et al, 2012 CVMA Proceedings) | |

Frequency (%) | Pedigrees |

25-50% | Exotic shorthair, British shorthair, Cornish Rex, Devon Rex |

5-25% | Abyssinian, Himalayan, Birman, Persian, Somali, Sphinx, Scottish fold, Japanese bobtail |

<5 | Maine coon, Norwegian forest cat, Domestic shorthair, Domestic longhair |

| 0 | Siamese, Burmese, Tonkinese, Russian blue, Ocicat, Oriental shorthair |

Red blood cell donation – who can donate blood?

In human medicine, the safety of the blood supply is critically tied to the quality and effectiveness of the pre-donation medical history, physical examination, and donor testing. The same can readily be said for veterinary medicine. Throughout the United States there are many animal blood banks from which veterinarians may purchase blood for transfusion. However many veterinary hospitals depend on voluntary donors to provide the blood necessary to meet the needs of the patients they serve.

Regardless from where the blood products are obtained, the donor screening process is one of the most important steps in protecting both the patient and the safety of the blood supply. The American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine, the organization that credentials all board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialists in the United States, has published infectious disease screening guidelines for blood donors. If you are interested in reading these guidelines, please click here.

Often I hear primary care colleagues say they have a donor dog or cat in their respective hospitals; often these animals are their own pets or belong to one of their team members. Unfortunately in my experience very few of these animals have been screened sufficiently to be blood donors, as this process is quite extensive and expensive. Similarly pet parents may be asked by a veterinarian to bring another animal from their residence to the hospital to donate for their sick pet. More than likely this other fur baby has not been adequately screened for infectious diseases.

If a blood transfusion is needed for a pet, I encourage pet parents to inquire whether or not the donor animal has been appropriately screened for infectious diseases.

In a true emergency situation, a veterinarian and/or family may not have the luxury of waiting for the ideal blood product to arrive, and thus they must accept the potential risks of transfusing a blood product that has not been suitably screened.

Are there complications associated with red blood cell transfusions?

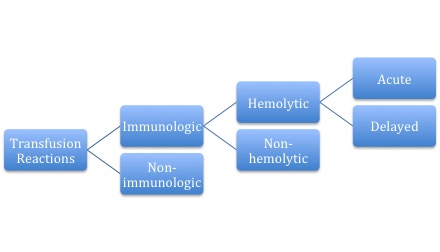

Transfusion reactions are classified as immunologic or non-immunologic; in other words, is the immune system involved in the reaction or not? Immunologic reactions may or may not result in the destruction of red blood cells (called hemolysis); those that do are the most serious!

The nature of immunologic transfusion reactions depends on whether the body has pre-existing molecules (called antibodies) that recognize the antigens on red blood cells to cause a reaction. Recall that blood groups are defined by the presence (or absence) of specific antigens on the surface of red blood cells, and dogs and cats are uniquely different in this regard.

Dogs: Dogs do not typically possess antibodies in their blood against antigens on red blood cells unless they have previously received a transfusion. Severe transfusion reactions characterized by rupture/hemolysis of red blood cells are possible in the following patient populations:

- Those who have previously been transfused with DEA 1-positive blood

- Those who have been pregnant with a DEA 1-positive offspring

To be as safe as possible, all dogs should have their blood type determined and should have their blood tested against the donor blood to ensure compatibility (called a crossmatch). In certain emergency scenarios for a patient who has never received a red blood cell transfusion, administration of DEA 1-negative blood without crossmatching is usually safe.

Cats: As mentioned earlier, cats are distinctive compared to dogs, as they normally have antibodies against the red blood cell antigens of another cat.

All cats should have their blood type determined, and should be crossmatched to ensure compatibility with the donor.

Severe transfusion reactions are possible when as little as 1 milliliter (mL) of Type A blood is administered to a cat with Type B blood. Red blood cells rupture during circulation (called intravascular hemolysis) within minutes to hours, and this destruction can lead to anaphylactic shock and death. Administration of Type B blood to a cat with Type A blood also results in a transfusion reaction, but thankfully it is typically milder in nature.

Type A cats must only donate to Type A cats. Type B cats should only donate to Type B cats.

Not all immunologic transfusion reactions result in red blood cell destruction (hemolysis). Some common non-hemolytic reactions include:

- Urticaria / hives

- Pyrexia / fever

- Pruritus / itchiness

These reactions are most often transient in nature and are not life threatening scenarios. Of course, not all transfusion reactions are immunologic in nature. Possible non-immunologic reactions include:

- Volume overload and congestive heart failure

- Vomiting

- Electrolyte changes (i.e.: high potassium, low calcium)

- Transmission of infectious diseases

- Sepsis – this rare and occurs if the blood transfusion as contaminated

The take-away about red blood cell transfusions for dogs & cats…

Transfusion therapy in veterinary medicine is now relatively commonplace, and allows veterinarians to effectively save the lives of many critically ill patients. Cats must always have their blood type determined, and should always be crossmatched to a potential donor. Dogs should similarly be tested prior to receiving a red blood cell transfusion, but in an emergency situation, a dog that has never received a blood transfusion may receive DEA 1-negative blood without crossmatching. A dog who has previously received a transfusion must always be crossmatched. Whether prepared in-hospital or purchased from a veterinary blood bank, a veterinarian should ensure transfused products are of a known blood type and are ideally collected from donors who have been screened to be free of infectious diseases.

To find a board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialist, please visit the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine.

To find a board-certified veterinary emergency and critical care specialist, please visit the American College of Veterinary Emergency and Critical Care.

Wishing you wet-nosed kisses,

cgb