Gastric dilatation-volvulus or GDV is a life threatening and rapidly progressive condition in dogs. Other common terms for GDV include:

- Bloat

- Gastric torsion

- Stomach torsion

- Twisted stomach

If not recognized and treated appropriately and immediately, affected dogs can painfully die. In this week’s blog post, I review the causes, clinical signs, and treatment of GDV in dogs.

GDV – What causes it?

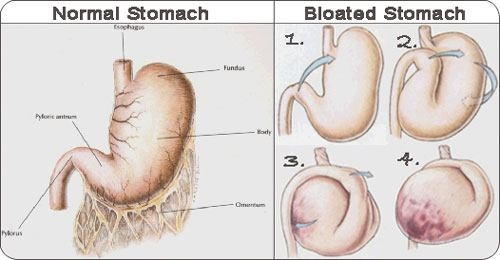

The hallmark feature of GDV is distention of the stomach with gas and/or food (dilatation) followed by twisting along its long axis (volvulus). Ultimately the gas and food can’t escape from the stomach and the pressure inside the stomach dramatically increases.

When the stomach is distended with gas and food to the point that it rotates on itself, there are numerous consequences, including:

- Blood from abdominal organs can’t get back to the heart

- The stomach wall doesn’t receive adequate blood supply

- The stomach wall can rupture

- The major breathing muscle (diaphragm) is compromised so the lungs can’t expand properly

- Small blood vessels that connect the stomach to the spleen can rupture

Gastric dilatation-volvulus can happen in any breed of dog. However several breeds are over-represented, particularly:

- Great Danes

- German Shepherds

- Standard Poodles

- Weimeraners

- Saint Bernards

- Irish Setters

- Gordon Setters

- Bassett Hounds

Unfortunately to date the definitive cause of GDV is not known. Multiple studies have attempted to identify risk factors for developing this potentially lethal condition. Based on these investigations, the following seem to consistently increase the risk of GDV:

- Body conformation: Deep-chested (relative to chest width) breeds are over-represented.

- Age: Older dogs are affected more commonly than younger ones.

- Temperament: Dogs characterized as “fearful” or “anxious” develop GDV more often than those deemed “happy” by their families.

- Feeding habits: Dogs only fed one time per day may be more affected than those fed more than one meal per day. Additionally dogs fed larger volumes of food per meal, as well as those who eat rapidly, may be at greater risk.

Other studies have identified some other potential risk factors, including:

- Dietary ingredients: A 2006 study showed dogs who ate food with an oil or fat ingredient that was listed in the first four ingredients on the food label had a 2.4-fold increased risk of developing GDV.

- Delayed transit of food out of the stomach: The findings of a 1992 study suggested GDV patients have delayed stomach-emptying times. However this investigation could not confirm if the delayed time was the cause or the result of GDV.

- Increased length of the ligament between the liver and stomach: A 1995 study showed GDV patients had a longer hepatosplenic ligament compared to dogs without GDV.

- Spleen: A 2013 study revealed dogs who previously had their spleen removed have been shown to have a 5.3 times greater risk of developing GDV.

- Family history: A 2000 study showed dogs who had a 1st-degree relative with a history of GDV were over-represented for developing this condition.

GDV – What are the clinical signs?

Immediate recognition of GDV is imperative for maximizing a positive outcome for an affected pet. Classic clinical signs that should raise concern for GDV are:

- Abdominal distension

- Restlessness / anxiety – an affected dog will often pant excessively and stretch

- Unproductive retching – vomiting without bringing up anything

- Excessive drooling

- Changes in breathing – dogs with GDV may breathe faster and/or have difficulty catching their breathes

- Inability to stand

Dogs with GDV rapidly develop shock, a condition in which the body’s tissues don’t get the oxygen supply they require to function properly. Without appropriate intervention, major organs (i.e.: liver, kidneys, heart) can begin to fail!

GDV – How is it diagnosed?

The diagnosis of gastric dilation-volvulus in dogs is relatively straightforward. Families bring to the hospital affected dogs with compatible clinical signs like abdominal distention, unproductive retching and excessive drooling. The veterinarian’s physical examination may identify changes in a pet’s breathing pattern, blood pressure, and/or heart rhythm. Non-invasive blood and urine tests are performed to screen for concurrent metabolic disturbances. Ultimately radiographs (x-rays) of the abdomen are needed to confirm a diagnosis of GDV.

The classic radiographic appearance of gastric dilatation-volvulus when a dog is lying on its right side is often called a “Smurf’s head”, “Popeye’s arm” or a “double bubble.”

GDV – How is it treated?

A veterinarian must immediately initiate steps to stabilize a dog with gastric dilatation-volvulus. Providing supplemental oxygen and intravenous fluids is imperative. Releasing excess gas from the stomach (called gastric decompression) is also of paramount importance, and may be achieved either by placing a tube down the esophagus into the stomach (called orogastric intubation) or placing a special catheter through the body wall into the stomach (called trocharization).

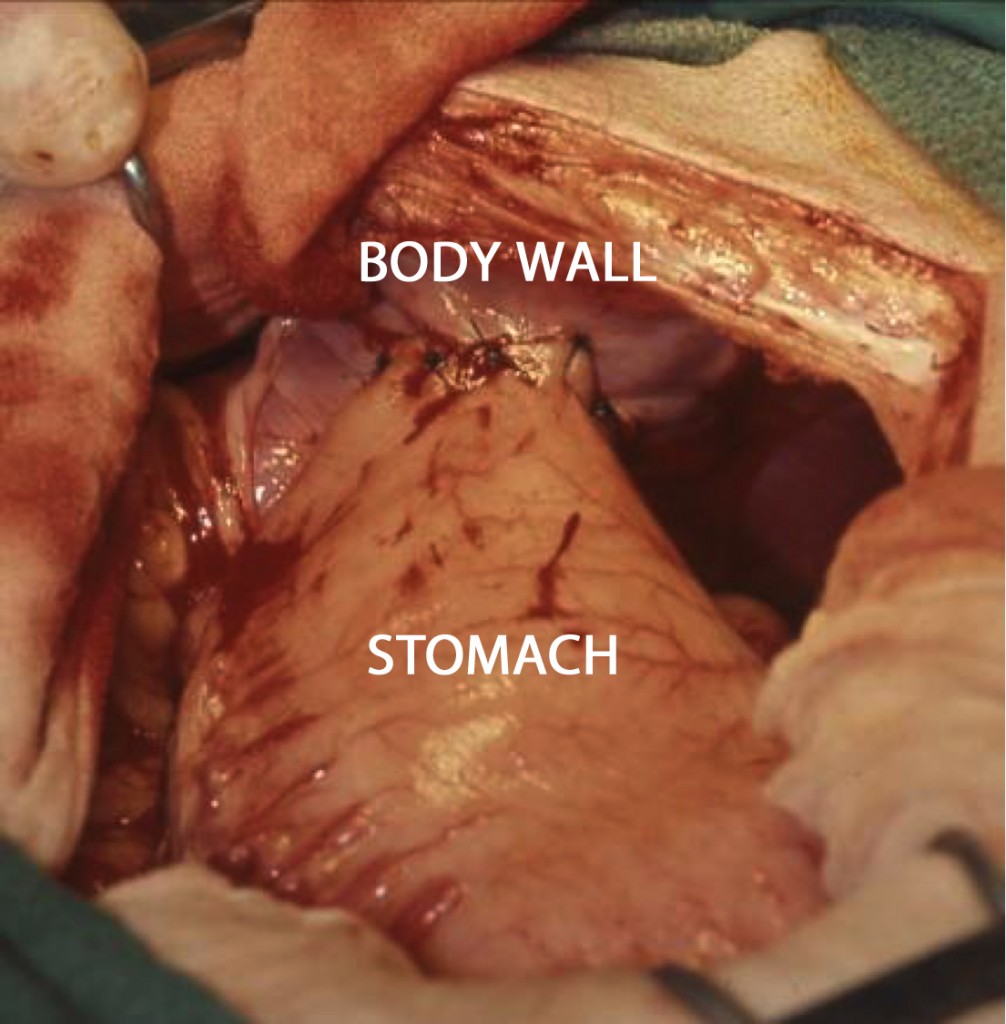

As soon as an affected dog is determined to be stable for anesthesia, surgery to de-rotate the stomach and place it back in its proper position is performed. A surgeon will also fully evaluate for damage the stomach wall and all other organs in the abdominal cavity, particularly the spleen. Ultimately to help ensure the stomach doesn’t rotate again, a procedure called a gastropexy is needed to permanently affix it to the abdominal wall.

The stomach has been surgically affixed to the abdominal wall. Photo courtesy of board-certified veterinary surgeon, Aylin Atilla, VMD, MS, DACVS

Gastric dilatation-volvulus has a reported mortality rate of approximately 15%. Based on numerous scientific investigations, mortality rates increase with the following:

- More than six (6) hours of clinical signs

- Abnormal heart rhythm prior to anesthesia and surgery

- The need of the surgeon to remove the spleen and/or part of the stomach wall

Many primary care doctors feel comfortable performing the necessary surgery to correct this condition. However because of the often-needed post-operative intensive care, some may recommend immediate referral to a veterinary specialty hospital where a team of board-certified veterinary surgeons and/or emergency/critical care specialists can attend to an affected pet.

The take-away message about GDV…

Gastric dilatation-volvulus is a potentially fatal condition of the stomach in dogs. Affected patients are profoundly uncomfortable, and often manifest clinical signs including distention of the abdomen, unproductive retching, drooling and anxiety. Immediate recognition of this problem, as well as expedient stabilization and surgical intervention are absolutely necessary to maximize the likelihood of a positive outcome.

I encourage you to watch a video about GDV by one my colleagues, Dr. Elizabeth Rozanski, another board-certified veterinary emergency/critical care and internal medicine specialist. To watch this informative presentation, please click here.

To find a board-certified veterinary surgeon, please visit the American College of Veterinary Surgeons.

To find a board certified veterinary emergency and critical care specialist, please visit the American College of Veterinary Emergency and Critical Care.

To find a board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialist, please visit the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine.

Wishing you wet-nosed kisses,

cgb