If you live in the United States, you probably know about the ongoing epidemic of canine influenza (sometimes called dog flu) in the Midwest. Veterinarians at the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s School of Veterinary Medicine have reported the virus has affected more than 1,000 dogs in Illinois, Wisconsin, Ohio and Indiana, and has resulted in the deaths of at least five dogs. Understandably pet parents in these areas and around the country are concerned. They’re scared. How did this happen? How do they protect their dogs? My goal in writing this post is to answer some of the common questions pet parents are asking their veterinarians.

Canine Influenza – What is it?

Canine influenza virus or CIV causes dog flu. To date two strains have been identified: H3N8 and H3N2, the latter being the strain implicated in the most recent outbreak in the Midwest. Some people have asked for what the “H”s and the “N”s stand. “H” stands for a glycoprotein called hemaglutinin and “N” stands for another glycoprotein called neuraminidase; the respective numbers tells us how many of each is present in the outer layer of the shell (called a capsid) that surrounds the virus. These glycoproteins have several important functions, particularly helping the virus gain entry into cells of the immune system.

Canine influenza virus was initially caused by equine influenza A H3N8 virus, and the first reported infections were documented in racing greyhounds in Florida in 2004. Essentially the virus “jumped ship” from horses and is now considered a dog-specific lineage of H3N8. The newest strain of canine influenza virus, H3N2, was first identified in southern China and the Republic of Korea in 2006, and infectious disease experts thought this strain was isolated only to parts of Asia. No one yet knows exactly how H3N2 came to the United States, but we know both strains of CIV are relatively new. Therefore the vast majority of dogs in the United States has never been exposed to them, and is thus susceptible to infection.

Canine Influenza Virus – How does it spread?

Canine influenza spreads either via respiratory droplets in the air (called aerosolized secretions) or via contaminated objects and people. The virus retains its ability to infect in the environment for several hours:

- Up to 48 hours on surfaces (i.e.: counters, etc.)

- Up to 24 hours on clothing

- Up to 12 hours on hands

Once exposed, dogs could begin to show clinical signs in approximately two to four days. Interestingly dogs are most contagious during this incubation period (the time from exposure to the development of clinical signs); furthermore they can continue to shed the virus for up to 10 days after onset of clinical illness. Approximately 20-25% of dogs exposed to the virus do not develop clinical signs, but still shed the virus, thus posing an infectious threat to other dogs. As I mentioned earlier, all dogs are susceptible to infection when first exposed to the virus because dogs don’t have natural immunity to the disease. So an infected dog housed in a boarding facility (or similar environment) could infect a meaningful number of co-kenneled dogs; more importantly most of these dogs will develop clinical illness.

Canine Influenza – What are the signs?

Dogs infected with CIV often have clinical signs similar to those caused by canine infectious respiratory disease complex (CIRDC), sometimes also called canine infectious tracheobronchitis and ‘kennel cough.” Dog flu is not a seasonal infection as it is in humans; dogs can become infected any time of year. Common clinical signs of CIV include:

- Coughing (dry or moist)

- Sneezing

- Fever

- Runny nose (nasal discharge can be clear to yellowish-green mucus)

- Eye discharge

- Rapid breathing

- Difficulty breathing

- Cyanosis (blue-tinged gums)

- Decreased (or loss of) appetite

- Decreased energy level

- Collapse

To date it appears the majority of dogs infected with CIV develop mild clinical signs that persist for 2-3 weeks despite treatments like cough suppressants. Affected dogs may have a soft, moist cough or a dry cough similar to that induced by kennel cough. Nasal and/or ocular discharge, sneezing, lethargy and anorexia may also be observed. Many dogs develop a purulent nasal discharge and low-grade fever. Occasionally (~20%) dogs develop life-threatening illness, including pneumonia, high fevers, and respiratory distress. The reported overall mortality rate for canine influenza is approximately 5%.

Canine Influenza – How is it diagnosed?

A veterinarian should evaluate dogs with respiratory clinical signs as soon as possible. Your family veterinarian will ask you several important questions about your pet’s environment and exposure to other dogs, and it is very important you provide as detailed answers as possible. The doctor will also perform a complete physical examination to look for clues about your pet’s illness. Your family veterinarian may recommend consultation with a board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialist due to the emerging nature of this disease.

The good news is there is a non-invasive blood test that can be performed to confirm canine influenza infection. Currently most reliable method for confirming infection is called serologic testing to identify special proteins called antibodies the body makes to fight the virus. However the body takes approximately one week to make antibodies, and thus one needs to analyze more than one sample of blood to accurately perform serologic testing. To perform serology analysis for canine influenza virus a small sample of blood is collected initially within the first seven days of illness and then again approximately two weeks later. Dog flu is diagnosed when there is a four-fold increase in the quantity of antibodies from the first sample to the second one (called a convalescent sample).

Your pet’s veterinarian may swab the inside of your pet’s nose (called a nasal swab) or the back of his/her throat (called a nasopharyngeal swab) for a non-invasive test called polymerase chain reaction or PCR. This test is commonly done for patients who have been sick for less than four days. If the PCR test is positive, the patient is most likely infected with canine influenza. However false negative results have been documented, and PCR testing is not recommended if a patient has been sick for more than four days.

Canine Influenza– How is it treated?

There are no specific treatments for canine influenza virus infection in dogs, and therapies are largely supportive in nature. Antiviral drugs that are often prescribed for people with the flu have little or no known efficacy or safety in dogs. With appropriate nutrition, oxygen therapy, various respiratory therapies (i.e.: thoracic physiotherapy or nebulization/coupage), maintenance of hydration, and good husbandry interventions, most dogs recover within 2-3 weeks.

As mentioned earlier, some dogs develop serious and potentially life-threatening illness, requiring aggressive critical care. For this reason your family veterinarian may recommend referral to veterinary specialty hospital where your pet can receive around-the-clock care from a board-certified veterinary emergency and critical care specialist and/or a board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialist.

Canine influenza – What is the risk to humans and cats?

Currently there is no evidence canine influenza virus H3N8 or H3N2 can be transmitted from dogs to people. Similarly there is no documentation of human infection with CIV. Nevertheless influenza viruses are constantly changing (just as H3N8 did when it “jumped ship” from horses to dogs), so it technically is possible for the virus to modify itself and infect humans. Thankfully current science tells us canine influenza viruses currently pose a low threat to humans. The latest strain of canine influenza virus, H3N2, can theoretically infect cats, but to date there have been no documented cases in felines.

Canine Influenza – What can you do to help?

Below are some key tasks you can do to help protect your fur babies:

- Avoid high-risk areas: Be cautious of visits to dog parks, dog shows and the groomers where there are bound to be many dogs. If you live in the area of the current H3N2 epidemic, this type of temporary precaution is profoundly important to help curb the spread of infection.

- Clean, clean and clean: Be sure you thoroughly disinfect your dog’s various items, including beds, harnesses, bowls, and leashes. Of course keeping the general environment to which your pets are exposed is also important. The good news is common disinfectants (i.e.: 10% diluted bleach) kill canine influenza virus, and proper hand washing can truly help reduce disease transmission.

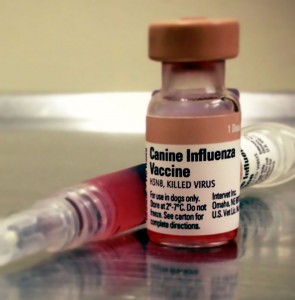

- Consider vaccination: There is an approved vaccination against canine influenza virus H3N8 strain. While vaccination doesn’t prevent disease, it does significantly reduce the severity of clinical signs and the amount of virus shed by infected patients. Currently we do not know if this vaccine is effective against the H3N2 strain, but experts suggest there may be some efficacy due to cross-reactivity. Studies are currently underway at the Animal Health Diagnostic Center at Cornell University’s College of Veterinary Medicine to determine the true efficacy of the current vaccine against H3N2. This specific vaccination is not considered a “core” vaccine, but rather a “lifestyle” one. Therefore not every dog should receive this vaccine, as it’s intended only for those at risk for exposure to canine influenza virus. Talk to your family veterinarian to find out if the canine influenza vaccine is right for your dog.

- Get your pet to a vet ASAP: As with most diseases, early identification and intervention is important. If you are concerned about your pet’s health for any reason, please seek immediate veterinary medical attention for him/her.

The take-away message about canine influenza…

Canine influenza, also known as dog flu, is relatively new virus. The first cases of the disease were documented in racing greyhounds in Florida in 2004, and patients were identified as having a strain called H3N8. Another strain called H3N2 was originally found in dogs in parts of Asia in 2006, but an epidemic of this infection is currently ongoing in some midwestern states of the United States. Clinical signs often mild, and include coughing, nasal and ocular discharge, fever, and reduced energy level. However approximately 20% of infected patients do develop potentially life-threatening complications like pneumonia, high fevers, and respiratory distress. Your family veterinarian should evaluate your dog as soon as possible if you observe any respiratory clinical signs, and consultation with a board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialist may be helpful to direct diagnostic and therapeutic interventions. Non-invasive testing is available to confirm a diagnosis of canine influenza, and treatment is largely supportive in nature. Most infected dogs will recover within 2-3 weeks.

To find a board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialist, please visit the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine.

To find a board-certified veterinary emergency and critical care specialist, please visit the American College of Veterinary Emergency and Critical Care.

Please consider sharing this information with other per parents, and don’t forget to find me on social media: