As a board-certified veterinary emergency and critical care specialist, I have to be prepared for the worst at any moment. What’s the worst? Death! Patients die, sometimes unexpectedly. Just as for humans, one can perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation or CPR in attempt to revive a pet who has experienced cardiopulmonary arrest (CPA). Performing CPR isn’t something only a veterinary healthcare team performs – pet parents can perform it too! This week I share information to help owners execute CPR at home should the need arise.

CPR – What is it?

CPR stands for cardiopulmonary resuscitation. It is necessary when patients experience cardiopulmonary arrest or CPA – this is the term used to describe cessation of spontaneous heart beat and breathing. There are two components to CPR:

Basic Life Support (BLS)

This is defined as maintaining airway patency and support breathing and circulation without the use of equipment and/or medications. Without question, BLS is the foundation for saving lives after CPA, and is characterized what should be done for patients with life-threatening injuries until they can be transported to a hospital to receive full medical care. Basic life support during CPR involves breathing for the patient and performing chest compressions.

Advanced Life Support (ALS)

This is defined as life-saving interventions that extend BLS to further support a patient’s circulation, maintain a patent airway, and provide adequate oxygenation & ventilation. Examples of ALS including defibrillating the heart (what doctors are doing when they use “the paddles” and yell “clear!”) and administering medications in an attempt to trigger spontaneous breathing and/or restart the heart.

While ALS is performed by trained medical professionals, pet parents are capable of performing BLS with proper knowledge and training. Performing high quality BLS has been documented to be an independent predictor of survival. Veterinarians and veterinary healthcare team members can become certified in BLS by completing an online course. Click here for more information.

CPR – How do I do it?

Pet parents are capable of performing single-rescuer BLS. This means they are by themselves, and the patient does not have an endotracheal tube in place. An endotracheal tube is a sterile hollow tube introduced through the mouth into the trachea (aka windpipe). Single-rescuer CPR has two components:

Chest Compressions

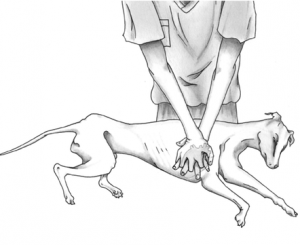

To perform proper chest compressions, appropriate body position and hand placement are essential.

- Hands should be placed directly over the heart in keel-chested dogs while they should be placed over the widest point of the thorax in large and giant breeds.

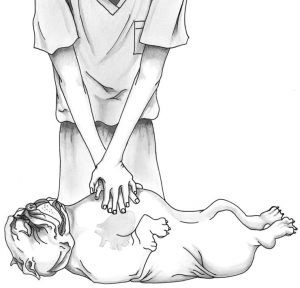

- Barrel-chested dogs may benefit from compressions being performed in dorsal recumbency with hands placed at the level of the xiphoid.

- In small dogs and cats, one hand is placed to allow direct compression of the chest cavity between the thumb and fingers at the level of the heart.

Rescuers should aim to compress the thoracic cavity ~30-50% at a rate of 100-120 compressions per minute. Compressing to the rhythm of “Stayin’ Alive” by the Bee Gees or the Imperial March (Darth Vader’s theme song) from Star Wars will help ensure one performs the proper number of chest compressions.

The chest should be allowed to completely recoil following each compression. Performing proper chest compressions is exhausting. Rescuer fatigue may lead to inadequate compression technique, so chest compressor should ideally be rotated every two minutes. Obviously, this isn’t an option if you’re by yourself, so do your best!

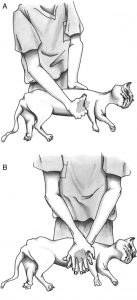

Ventilation

A single rescuer should firmly hold the patient’s mouth closed and extend the neck while maintaining alignment with the back. Rescuers should form a tight seal over the patient’s nose with their mouths and blow firmly into the nose to inflate the chest.

You should observe a rise of the thoracic cavity and target an inspiratory time of one second. The compression:ventilation (C:V) ratio should be 30:2 – this means you perform 30 chest compressions, then delivery 2 proper breaths, and repeat the cycle for as long as needed. Please watch the video below of a demonstration of single-rescuer CPR / BLS created by Dr. Janet Olson, a board-certified veterinary cardiologist.

CPR – Will my pet survive?

This is an important question. Most pet parents have watched a television medical drama like ER or Chicago Med. When a human patient on one of those shows experiences CPA, it seems like all it takes to bring them back is to defibrillate them (again, using “the paddles” and yelling “clear!”).

If only CPR was as easy as in the clip above! Despite efforts, prognosis for veterinary patients who experience CPA is generally grave. One study documented a 5.8% overall survival rate. Interestingly, CPA due to anesthesia complications have better outcomes. A study showed a survival rate of 36.4% in cats experiencing an anesthesia-related CPA while none of those who experienced a CPA in an intensive care unit (ICU) survived. A more recent review of 43 cats with CPA documented an overall discharge rate was 6.9%.

The take-away about CPR in dogs & cats

Pet parents are capable of performing single-rescuer CPR with proper training. With basic life support, including providing chest compressions and artificial breathing, patients can survive. Pet parents with a pet who has experienced cardiopulmonary arrest should perform high-quality BLS and transport their pet to the closest veterinary medical facility for complete care. All pet parents are strongly encouraged to learn CPR, and the American Red Cross offers training in BLS. Learn more here.

To find a board-certified veterinary emergency and critical care specialist, please visit the American College of Veterinary Emergency and Critical Care.

Wishing you wet-nosed kisses,

CriticalCareDVM