When most pet parents think of think of tick-borne diseases affecting pets, they think about infections in dogs. Common examples of such ailments in dogs are Lyme disease (borreliosis), ehrlichiosis, Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (rickettsiosis), babesiosis, bartonellosis, anaplasmosis, and hepatozoonosis. Yet we should not forget about cats! They, too, can be infected by the bite of a tick. This week I share some information about a potentially lethal tick-borne infection in our feline friends – cytauxzoonosis. Happy reading!

Cytauxzoonosis – What causes it?

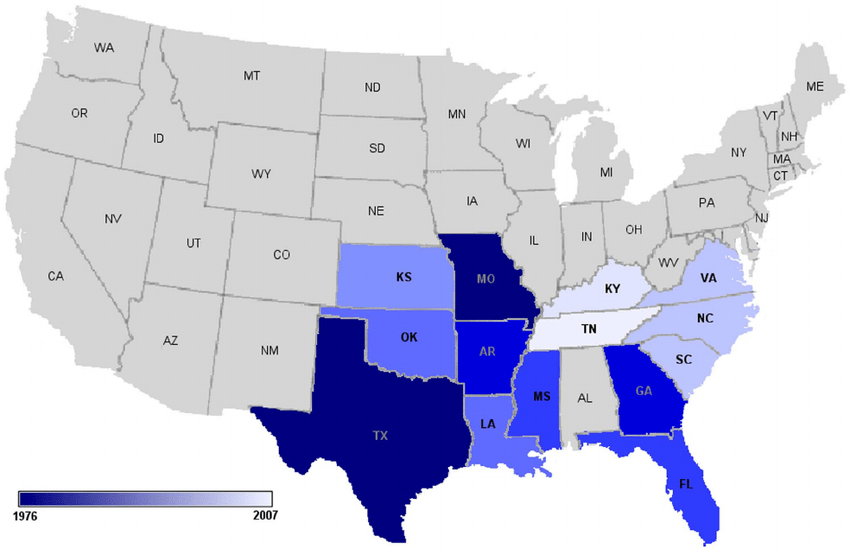

A protozoal organism called Cytauxzoon felis is most commonly transmitted through the bite of a species of tick called Dermacentor variabilis. Other tick species, including Amblyomma americanum, may also be involved in disease transmission.

In the United States, these ticks are found in the south central, southeastern, and mid-Atlantic regions of the country. Cytauxzoonosis infection has been confirmed in wild cats too, including bobcats, Florida panthers and Texas cougars.

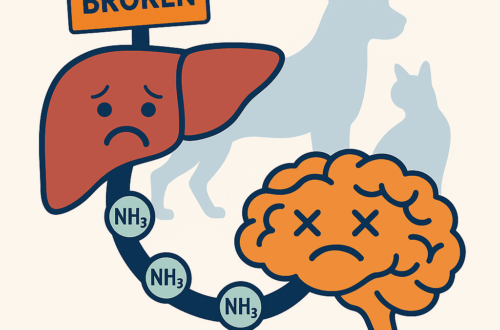

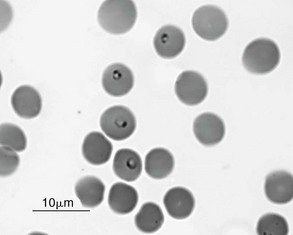

There are two distinct forms of Cytauxzoon spp.: sporozoite and erythrocyte or piroplasm. Ticks transmit the sporozoite to a cat, which then invade specific cells (called reticuloendothelial cells) throughout the body. Sporozoites then reproduce so the cells become large enough to cause occlusion of blood vessels in multiple organs. This vessel congestion ultimately causes dysfunction of major body organs and ultimately death. The organisms subsequently infect more white blood cells and erythrocytes. The erythrocyte or red blood cell form – called a piroplasm – looks like a round-to-oval signet ring. Piroplasms reproduction and ultimately destroy red blood cells to cause a form of hemolytic anemia.

Cytauxzoonosis – What does infection look like?

Cats of any age and sex can be infected, but younger cats are over-represented. Infections are most commonly identified in the early spring to early fall when ticks are most active. Clinical signs appear quickly, and the disease progresses very rapidly. Common signs include:

- Anorexia

- Altered level of consciousness

- Seizures

- Lethargy

- Icterus (yellowing of the skin and “whites” of the eyes)

- Pale gums

- Fever

- Difficulty breathing

Cytauxzoonosis – How is it diagnosed?

A veterinarian will perform a complete physical examination. Abnormalities will typically be quite evident. In addition to the clinical signs mentioned earlier, an enlarged liver and spleen are also quite common.

The doctor will also perform some non-invasive blood and urine testing. These tests seek not only to confirm a diagnosis of cytauxzoonosis, but also to identify dysfunction in major organs triggered by infection. Partnering with a board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialist can be unquestionably helpful for diagnosing this infection as quickly as possible.

Cytauxzoonosis – How is it treated?

Unfortunately, a standard treatment for cytauxzoonosis has not yet been identified. This is an active area of research for board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialists who have a special interest in infectious diseases.

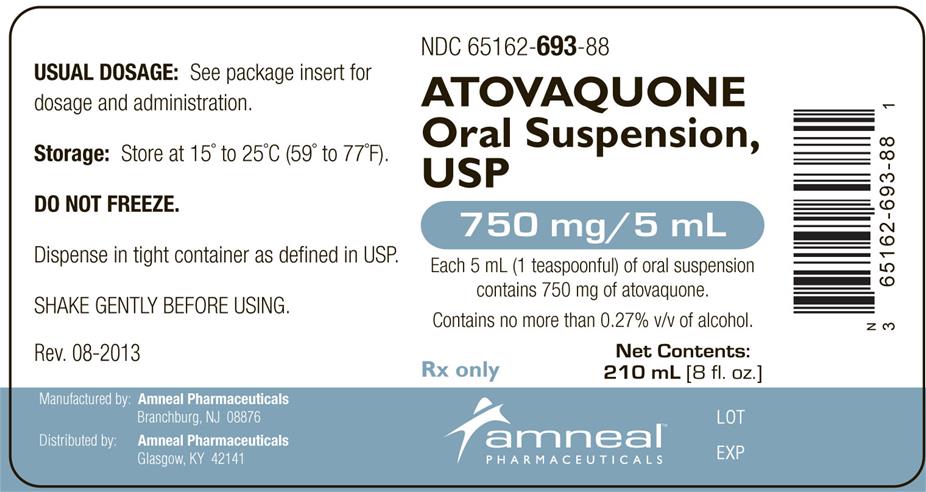

Based on some recent research, hospitalization for aggressive treatment with a unique “cocktail” of medications – imidocarb dipprioionate, atovaquone, azithromycin, heparin, and atropine – resulted in improved survival. This treatment protocol had a 60% survival rate compared to 26% when only imidocarb diproprionate was given to infected cats. Without treatment, survival rate is reportedly 3%.

The take-away message about cytauxzoonosis…

Ticks can infect cats with certain organisms, including that which causes cytauxzoonosis. Early identification and aggressive therapy are key to a successful outcome. Treatment that includes administration of a medication called atovaquone has been associated with higher survival rates. Partnering with a board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialist can be invaluable for developing logical and cost-effective diagnostic and treatment plans.

To find a board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialist, please visit the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine.

Wishing you wet-nosed kisses,

cgb