A common reason for pet parents to bring their dogs and cats to the family veterinarian is an observable increase in thirst (called polydipsia or PD) and/or increased volume of urination (called polyuria or PU). A pet parent can’t keep a pet’s water bowl filled enough and/or the pet seems to “pee a river!” There are many potential causes of excessive urination and thirst, and often working with a board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialist early in the course of a pet’s illness is both medical and financially beneficial.

Confirming excessive urination and thirst…

The first step in the diagnostic investigation of pet’s reported excessive urination and thirst is to confirm the parent’s perception is accurate. As there is a relatively wide normal range of water intake for both dogs and cats, it is always important to ensure there is actually a true problem before performing more tests and spending more money. Confirming excessive urine production requires the collection of all of the urine produced by a pet in a 24-hour period. This is understandably labor-intensive, especially for cats, and thus is a task not commonly undertaken. In contrast measuring a pet’s daily water consumption is relatively simple; one just needs to allow the pet to drink normally during a 24-hour period while always recording the amount of water offered. Then one calculates the difference between the amount offered and the amount remaining at the end of the 24-hour period. Dogs and cats normally drink less than 100 milliliters of water per kilogram of body weight per day (<100 mL/kg/day).

My pet, indeed, drinks too much…now what?

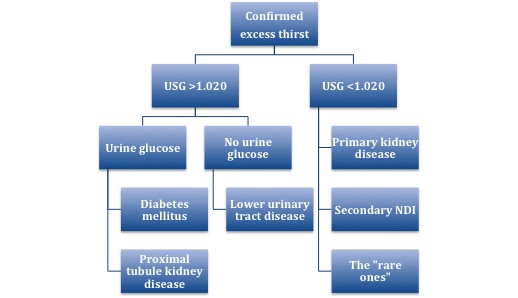

Once confirmed that a pet is truly drinking an excessive amount of water in a 24-hour period (>100 mL/kg/day), the family veterinarian will recommend some non-invasive urine and blood tests. The urine sample evaluated should be a pet’s first urine of the day, and pet parents should collect such a sample in preparation for their fur baby’s appointment. Initial tests are commonly called a minimum database or MDB, and include a complete blood count (CBC), biochemical profile (CHEM) and urinalysis (UA). The UA is an absolutely essential test, as the medical team must evaluate the concentration of the urine. Urine concentration, also known as urine specific gravity (USG), is a vital measurement that helps a family veterinarian develop a plan to learn of a pet’s definitive diagnosis. In general, a urine specific gravity >1.020 suggests a one list of possible diseases while a concentration <1.020 suggests another one.

Patients with USG >1.020 should be assessed for evidence of excess glucose/sugar in the urine. Lower urinary tract diseases (i.e.: urinary bladder stones, urinary tract infection, cancers) are most likely in those without urine glucose/sugar, while diabetes mellitus (i.e.: sugar diabetes) and a disorder of part of the kidneys called the proximal tubules would be suspected for those with urine sugar. In my experience, patients with excessive thirst more commonly fall into the category of having a USG <1.020, and this is probably because there are more disease possibilities. In addition to chronic kidney disease, there are two other groups: secondary nephrogenic diabetes insipidus and a cluster affectionately called the “rare ones.”

Diabetes insipidus

When one reads the term diabetes insipidus, one may think of elevated blood glucose or sugar – diabetes mellitus. But diabetes mellitus is very different from diabetes insipidus (DI). Diabetes insipidus is a condition characterized by excessive thirst and urination of large amounts of markedly diluted urine; additionally a reduction of fluid intake has no effect on the concentration of urine. There are two major types of DI: nephrogenic (arising from the kidneys) and central (arising from the brain). Nephrogenic diabetes insipidus (NDI) results from an insensitivity of the kidneys to anti-diuretic hormone (ADH), a hormone that helps the body retain water. Central DI (CDI) is the result of a lack of ADH production by the hypothalamus in the brain; CDI is considered one of the “rare ones” and will be discussed later in this post. Nephrogenic diabetes insipidus can be primary (a rare congenital defect of the kidneys that is also classified as one of the “rare ones”) or secondary (caused by diseases that affect the kidneys). There are many causes of secondary NDI, including:

- Low potassium

- Elevated calcium

- Low sodium

- Cushing’s disease (excess production of the body’s own steroid called cortisol by the adrenal glands)

- Addison’s disease (inadequate adrenal gland function)

- Pyometra (uterine infection)

- Liver dysfunction

- Acromegaly (growth hormone abnormality in cats)

- Pyelonephritis (kidney infection)

- Hyperaldosteronemia (elevated of a hormone called aldosterone)

- Hyperthyroidism (elevated thyroid hormone concentration)

- Certain drugs (i.e.: steroids, diuretics, anti-seizure medications)

Unfortunately investigating the causes of secondary NDI is something that is very rarely done thoroughly. Working with a board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialist to help develop a diagnostic plan can be invaluable for both investigative and financial efficiency.

The “rare ones”

So far I have introduced two of the three “rare ones” – central diabetes insipidus and primary nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. The last is called psychogenic polydipsia (PP) and is a behavioral disorder of increased thirst. These “rare ones” are indeed just that – rare! During my internal medicine residency, mentors repeatedly imparted the following mantra:

“If you think you have a patient with CDI, primary NDI and PP, think again! And then think again! And then think again, again!”

Despite the rarity of these conditions, it has been my experience during the past 11+ years that many primary care doctors immediately jump to one of these diagnoses and subsequently perform testing to identify one of them. The issue with this approach is that investigation for the “rare ones” can actually be potentially dangerous if not performed correctly or at the proper time! A test utilized to differentiate CDI, primary NDI and PP from each other is a modified water deprivation test (MWDT); this test requires a purposeful but controlled water restriction for the affected pet and necessitates very close monitoring. Performing a MWDT and restricting water without first eliminating other diseases that can cause excessive thirst and urination from the list of possibilities can be very dangerous. Indeed, there are reports of patient death when testing is not performed properly. Water restriction is very rarely indicated and often can be harmful to pets! Only once kidney disease and all possible causes of secondary NDI have been ruled out should a clinician consider testing for CDI, primary NDI and PP.

The take-away message about excessive thirst & urination…

There are many diseases that cause excessive urination and thirst in dogs and cats. Determining the true reason can be challenging, and often requires a series of non-invasive and minimally invasive tests. Working with a board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialist can be instrumental for developing the most logical and cost-effective diagnostic plan. Internal medicine specialists are ready and willing to partner with your pet’s family veterinarian to help ensure your pet receives the best possible healthcare.

To find a board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialist, please visit the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine.

Wishing you wet-nosed kisses,

cgb