In previous posts I’ve written about some important neurological conditions that affect our pets, including intervertebral disc disease (IVDD) and brain tumors. This week’s post reviews insightful information about another neurological condition called fibrocartilaginous embolism or FCE. I hope you enjoy reading it and will share it with other pet owners. Happy reading!

What is a fibrocartilaginous embolism?

To understand what a fibrocartilaginous embolism is you need to have a basic understanding on the anatomy of an intervertebral disc. Intervertebral discs are found between vertebrae, the individual bones that form the back. They have two major components – an outer fibrous ring called the annulus fibrosis and an inner gel-like substance called the nucleus pulposus. For me, I like to think of intervertebral discs as jelly donuts. The dough is the annulus fibrosis and the jelly is the nucleus pulposus.

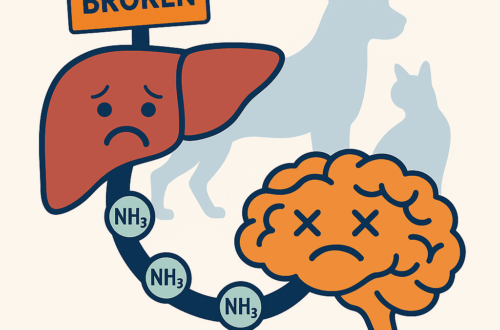

A fibrocartilaginous embolism is thought to be an insult to the spinal cord due to fibrocartilage from the nucleus pulposus (aka: the jelly from the jelly donut) acutely disrupting blood supply focally to the spinal cord. Other terms and phrases for FCE are fibrocartilaginous embolic myelopathy and spinal cord stroke.

What does an FCE look like?

Fibrocartilaginous embolism is more common in dogs than cats. Large and giant breed dogs are over-represented, but any breed may be affected. Dogs are usually young to middle-aged with a mean age of 5.5 years. There is no documented sex predisposition.

Clinical signs of FCE depend on the region of the spinal affected by the vascular insult and the severity of the lesion. The most common locations are the thoracolumbar spinal cord and the cervical (neck) spinal cord. This problem is usually temporally associated with meaningful physical activity like playing fetch. Clinical signs occur all of sudden, often progress within a few hours, and typically affect one side of the body more than the other. Although neurologic deficits can be meaningful, FCE is not painful after the initial vascular insult to the spinal cord.

How is an FCE diagnosed?

Veterinarians will recommend advanced diagnostic imaging tests to both confirm the presence of FCE and to rule out other causes of a pet’s neurologic deficits. These tests may include:

- Contrast radiography (myelography) – injecting a special dye in the space around the spinal cord may reveal evidence of spinal cord swelling

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) – this is the imaging modality of choice for FCE

- Cerebrospinal fluid analysis – fluid evaluation may identify evidence of inflammation and/or infection

These advanced imaging tests are not widely available through primary care veterinarians. As such, families are often referred to veterinary referral hospitals to partner with board-certified veterinary neurologists.

How is an FCE treated?

Currently, there are no specific therapies to treat fibrocartilaginous embolism in dogs and cats. Rehabilitation therapy is pivotal to maximizing the likelihood of a meaningful functional recovery. Key components to rehabilitative care include:

- Providing plush/soft bedding at all times

- Repositioning pets every 4-6 hours to prevent the formation of breathing problems (e.g.: pneumonia) and decubital ulcers (aka bed sores)

- Urinary bladder expression (if needed)

- Passive range of motion exercises

- Assisted exercises (e.g.: use of slings/harnesses & yoga balls)

- Neuromuscular electrostimulation

- Hydrotherapy

Most dogs begin to improve neurologically within a couple of weeks of vascular insult. Meaningful improvement is often seen within several weeks, and published functional recovery rates are 50-84%.

The take-away message about fibrocartilaginous embolism in dogs & cats…

Fibrocartilaginous embolism or FCE is a vascular insult to the spinal cord. This problem may cause a variety of neurological deficits. Advanced diagnostic imaging is required for definitive diagnosis. Rehabilitation therapy is essential to maximizing the likelihood of a functional outcome.

To find a board-certified veterinary neurologist, please visit the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine.

Wishing you wet-nosed kisses,

CriticalCareDVM