Last week I provided information about urinary tract infections (UTIs) in dogs and cats, and the feedback from readers like you was very positive. Thank you for reading! This week I discuss another troublesome lower urinary tract disease, one that affects cats and can have identical clinical signs as UTIs. This syndrome is called feline idiopathic (interstitial) cystitis (FIC), and is one often confused with infections of the lower urinary tract.

FIC – What is it?

Cystitis means inflammation of urinary bladder, and thus one may logically assume the main issue in cats with FIC is associated with this organ. Yet such an assumption would not be entirely accurate. Cats with FIC often have abnormalities in several other organs so there is no “one” abnormality that causes FIC in cats; this fact has led many veterinarians to refer to FIC as a “Pandora Syndrome.” Three areas of the body that seem to be over-represented are:

- Urinary bladder wall: Changes to the cells lining the inside of urinary bladder (called uroepithelia), as well as abnormal concentrations of specific proteins in the urine (called glycosaminoglycans or GAGs), can change the permeability of the blood vessels in the wall of the urinary bladder to cause swelling/edema and leakage of red blood cells into urine.

- The stress response system of the brain: Families of FIC cats often describe their bur babies as having “high anxiety” or being “easily stressed.” Chronic activation of the body’s stress response system (called the sympathetic nervous system) can actually alter the permeability of the blood vessels in the wall of the urinary bladder wall and induce marked inflammation (called neurogenic inflammation).

- The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis: Normally the hypothalamus and pituitary gland secrete specific hormones (corticotropin-releasing hormone/CRH and adrenocorticotropic hormone/ACTH, respectively) that cause the adrenal glands to secrete a hormone called cortisol. The activity of these hormone-secreting organs increases during periods of stress, yet in cats with FIC there is evidence the adrenal glands don’t (or aren’t able to) respond adequately to stimulation.

FIC – What the clinical signs?

Cats with idiopathic (interstitial) cystitis can show many clinical signs, most notably:

- Prolonged squatting or straining in and out of the litter box with little or no urine elimination – please note pet parents often confuse this with constipation

- Frequent urination

- Vocalization (e.g.: meowing, howling) while urinating

- Urinating outside the litter box, often in unusual locations (e.g.: potted plants)

- Blood in the urine (called hematuria)

- Frequent cleaning/licking of the genitals

FIC – How is it diagnosed?

There is no specific diagnostic test for FIC, and thus diagnosis necessitates exclusion of all other diseases that can cause lower urinary tract signs, particularly:

- Bacterial urinary tract infection (UTI)

- Cancer

- Anatomical abnormalities

A veterinarian should perform initial blood and urine tests to screen for systemic/metabolic diseases and infections; these tests include:

- Complete blood count (CBC): a non-invasive test that measures red blood cells, white blood cells, and clot-forming cells called platelets

- Serum biochemical profile (CHEM): a non-invasive blood test that screens for evidence of liver and kidney dysfunction, as well as abnormalities in electrolytes (e.g.: sodium, potassium, chloride)

- Urinalysis (UA): a non-invasive test to measure the concentration of urine, as well as to check for the presence of white blood cells, crystals, red blood cells, protein, and bacteria in urine

- Urine culture & sensitivity (UCS): the definitive test to both confirm the presence of bacteria in urine and to determine the most appropriate antibiotic to treat the infection

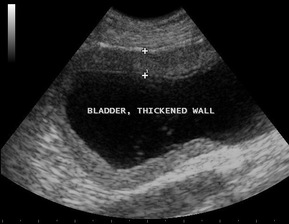

- Imaging of the urinary bladder: a veterinarian may recommend performing abdominal radiographs/x-rays or abdominal ultrasonography to screen for the presence of urinary bladder stones (called cystoliths or uroliths) and/or masses

Common findings in the urine of affected cats are the presence of many red blood cells and few white blood cells but no bacteria; however such results are not diagnostic for FIC. Recent experimental studies has begun to shed light on some future possible tests that may be useful in diagnosing this condition in cats, including:

- Infrared microspectroscopy

- Urinary glycosaminoglycan excretion

- Urinary trefoil factor 2 measurement

I’m hopeful continued research will lead to meaningful discoveries of clinical markers to help us diagnosis this complicated disease.

FIC – How is it treated?

Cats with FIC are typically presented to their family veterinarian for one of four reasons:

- Singular acute manifestation of clinical signs related to FIC (80-95%)

- Recurrent episodes of clinical signs related to FIC (2-15%)

- Persistent clinical signs of FIC that never fully go away (2-15%)

- Urethral obstruction in a male cat living with FIC (15-25%)

Given these possible presentations, the goals of therapy for cats living with FIC are:

- Decrease the severity and duration of clinical signs during an episode/flare-up

- Increase the length time between episodes

- Decrease the severity of clinical signs in those cats with persistent of FIC

Cats showing clinical signs of FIC are in pain. Therefore it is crucial affected pets receive appropriate pain medications to keep them as comfortable as possible during an episode / flare-up. Clinical signs often resolve on their own within 1 week without treatment (other than pain medication) in ~85% of cats; however the recurrence rate of these signs is very high within 6-12 months. If clinical signs persist for more than 7 days, additional interventions are justified.

Dr. Dennis Chew, a fellow board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialist and preeminent expert of the urinary tract in dogs and cats, has described FIC patients as “sensitive cats in a provocative environment.” Believe it or not, an indoor environment can be provocative for some cats – the monotony and predictable nature of such an environment can actually be stressful for some of our feline fur babies. With that being said, I am not advocating for or recommending an indoor/outdoor lifestyle for cats because such an environment invites unwelcomed exposure to infectious diseases and a potential for a plethora of accidents.

Clinical evidence suggests we have to make the indoor environment as appealing to cats as possible. Thus it is absolutely essential that treatment(s) for FIC include an ardent attempt to identify and remove (or modify) anything that could provoke affected patients – this practice is called multimodal environmental modification or MEMO.

Possible provocateurs include:

- Insufficient availability of water

- Unsuitable diet

- Food/water bowl issues (e.g.: inadequate cleaning, placement near loud appliances, requirement to share bowls, etc.)

- Litter box hygiene & management issues (e.g.: improper and/or inadequate cleaning; placement near loud appliances, not enough boxed available in residence)

- Inadequate number of vertical and horizontal perches in residence

- Construction in or around a residence

- Introduction (or loss) of human and/or animal family members

- Changes to normal routines

- Insufficient interaction between affected cat and pet parents

Working with a board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialist or board-certified feline specialist can be invaluable when trying to both identify stressors in your residence and implement MEMO in your household. Remember MEMO is simply a package of recommendations to help reduce or eliminate stressors in a cat’s environment, and a thorough evaluation of both patient and its environment are essential for developing the best treatment recommendations for an affected cat.

Antibiotics are not indicated for the treatment of FIC. However certain other drugs may have a place in the treatment of FIC. However these should not be used until appropriate medications have been prescribed and MEMO has been implemented. Partnering with a board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialist or board-certified feline specialist can be helpful to determine when additional drug therapy is appropriate for your fur baby.

The take-away message about FIC…

Feline idiopathic (interstitial) cystitis is complex disorder most often recognized in cats characterized as “sensitive” by their families. Treatment must include the provision of appropriate pain medication(s), as well as an attempt to identify and modify any stressor in a cat’s environment. Consulting with a board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialist or board-certified feline specialist can truly be helpful for developing an efficient diagnostic and therapeutic plan for affected patients.

To find a board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialist, please visit the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine.

To find a board-certified feline specialist, please visit the American Board of Veterinary Practitioners.

Wishing you wet-nosed kisses,

cgb