Dogs, like people, can be afflicted with problems of the spinal column. One of the most common issues with this part of the body is an abnormality of the intervertebral discs. This week I discuss acute intervertebral disc disease(IVDD) in dogs, and I hope you find the information helpful and share-worthy. Happy reading!

Intervertebral Disc Disease – What is the disc?

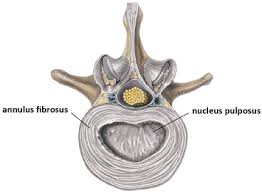

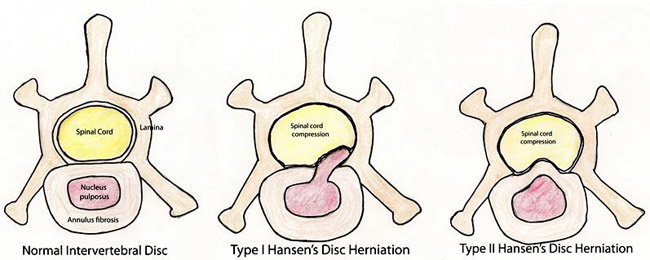

An intervertebral disc is a found between each bone of the spinal column (called vertebrae), and helps to stabilize the back by acting like a shock absorber. There are 7 cervical/neck vertebrae, 13 thoracic/chest vertebrae, 7 lumbar/lower back vertebrae, 3 fused sacral vertebrae, and a variable number of caudal/tail vertebrae. I like to think of each intervertebral disc as a jelly donut. Each disc has a thick outer portion (called the annulus fibrosis) composed of interwoven fibrous tissue (i.e.: the dough) and a center filled with a gel-like substance (called the nucleus pulposus) made of fluid and cartilage (i.e.: the jelly).

There are different types of acute intervertebral disc disease (IVDD):

- Acute non-compressive nucleus pulposus extrusion (ANNPE) – the nucleus pulposus is ejected forcefully from the intervertebral disc and subsequently bruises but does not compress the spinal cord

- Hydrated nucleus pulposus extrusion (HNPE) – the nuclear pulposus is ejected from the intervertebral disc and subsequently damages and compressed the spinal cord; the nuclear pulposus remains relatively liquified

- Fibrocartilagenous empbolic myopathy (FCEM) – read more about FCEM here

- Hansen type I intervertebral disc extrusion – very similar to HNPE; the major difference is the nucleus pulposus is contains less water and is thus considered dehydrated or degenerated

- Hansen type II intervertebral disc extrusion – the entire intervertebral disc shifts to compress the spinal cord; the nuclear pulposus is not ejected from the disc

Intervertebral discs normally degenerate as dogs get older. However, some breeds are predisposed to intervertebral disc disease because they are born with a defect in the development and maturation of their cartilage, including that in the discs. These dogs are called chondrodystrophoid and include:

- Dachshunds

- Bassett Hounds

- Pekingese

- Lhasa Apsos

- Shih Tzus

- French bulldogs

- Beagles

- Cocker Spaniels

What does IVDD look like?

As mentioned earlier, the most commonly affected dogs are chondrodystrophoid. The peak age of onset is 4-8 years of age, but some dogs are presented with clinical signs as early as 2-3 years of age because their intervertebral discs begin degenerating within the first two years of life. The most common clinical sign of intervertebral disc disease is pain. This discomfort is the result of either internal degeneration of the disc (called discogenic pain) or displacement of disc material into the region above the intervertebral space (called the vertebral canal). The vertebral canal is a space that houses the spinal cord and nerve roots that leave the spinal cord and travel to various parts of the body. Displaced disc material puts pressure of the spinal cord and/or nerve roots to cause pain and possibly neurologic signs.

Pain may manifest in any number of ways depending on the individual dog, the area of the spinal cord affected, and the severity of degeneration/injury (see Table #1).

| Table #1: Common Signs of Pain in Patients with Intervertebral Disc Disease | |

Site | Clinical Signs |

Neck |

|

Back |

|

Neurologic deficits manifest when disc material displaces compresses the spinal cord. I think of the spinal cord as a tree trunk with rings. Using this analogy, when the outermost rings are compressed, common clinical signs are referable to coordination and fine motor skill deficits, and include stumbling, a tendency to trip, unsteadiness in the gait, and knuckling over of the toes. The latter is called a conscious proprioception deficit. As deeper rings become involved (i.e.: there is more compression), dogs have difficulty rising and walking, and they may drag one or more of their legs because their strength has been affected. Ultimately with marked spinal cord and/or nerve root compression, pets become paralyzed and lose the ability to feel an affected leg(s).

How is IVDD diagnosed?

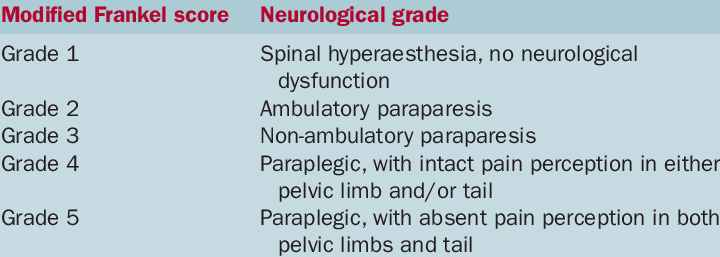

When a dog is presented for evaluation of possible intervertebral disc disease, a veterinarian will perform a complete physical examination, including an extensive neurologic evaluation. The doctor will categorize a pet into one of six categories based on the severity of their clinical signs in a scale known as the Modified Frankel Scale or MFS:

As there are other conditions that can affect the spinal cord and vertebrae (i.e.: vertebral tumors, infection, fractures), diagnostic imaging is required. The first test performed is radiography (x-rays), and patients often must be immobilized with sedation or anesthesia to obtain diagnostic quality images. Normal and most degenerating intervertebral discs are invisible on radiographs, and thus displacement may occur without radiographic evidence. Radiographs are helpful to screen for fractures and evidence of bone destruction from tumors. Due to the limited utility of radiography, advanced imaging is needed to determine the specific site of IVDD. The most common advanced imaging modalities are:

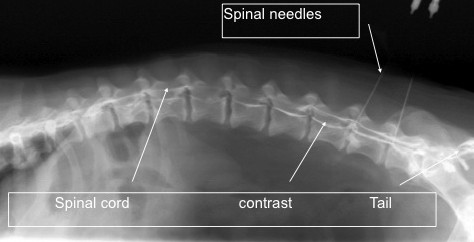

- Myelography: This is a specialized technique performed under general anesthesia that involves taking a radiograph of the spine after injecting a contrast agent/dye via a spinal tap (called a lumbar puncture) to surround the spinal cord and highlight the previously invisible spinal cord.

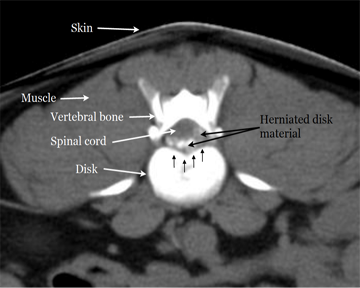

- Computed Tomography (CT scan): This is very unique imaging technique that produces cross-sectional images of the spine and intervertebral discs, and is often used in combination with myelography.

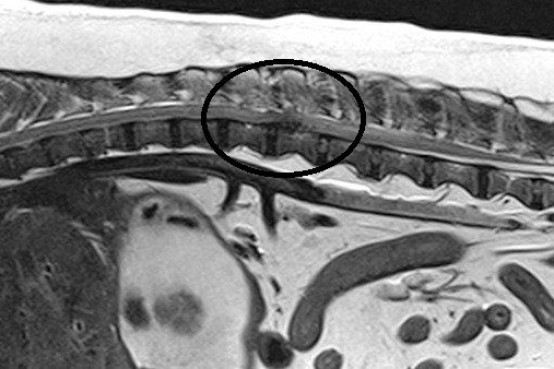

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): This modality is considered the gold standard for the spine because it is non-invasive and produces the most detailed images. A major benefit of MRI is it allows differentiation of the type of acute IVDD. Availability of MRI is typically limited to veterinary specialty referral hospitals.

How is IVDD treated?

The primary goals of treatment for patients with IVDD are to eliminate clinical signs of illness and prevent recurrence. These goals may be achieved either through medical therapies or surgical intervention depending on the severity of injury. Consultation with either a board-certified veterinary neurologist and/or surgeon is strongly recommended to help decide the most appropriate course of action for affected pets.

Medical Management:

Therapies without surgery are commonly prescribed for patients with only pain and/or very minimal non-progressive neurologic deficits. Strict confinement in an appropriately sized kennel or pen is of paramount importance. The period of confinement is variable, but is often at least three weeks long. Confinement is frequently much more challenging for pet parents than for pets, as dogs readily adjust to their temporary restrictions and are often more restful in their kennels. During confinement, aggressive pain management, anti-inflammatory medications, and/or muscle relaxants are prescribed to facilitate the healing process. If there is not a prompt response to aggressive medical management, the patient should be considered a candidate for surgical intervention. Unsatisfactory outcomes are almost always the result of inadequate confinement. After a defined period of strict confinement, dogs are allowed to gradually resume normal activities over a specific time period. Consultation with a board-certified veterinary sports medicine and rehabilitation specialist or a certified canine rehabilitation practitioner can be invaluable for helping prevent recurrence of clinical signs.

Complementary treatments may be appropriate adjuncts to traditional therapies. Acupuncture performed by a Certified Veterinary Acupuncturist and/or laser therapy performed by an appropriately trained individual may be helpful interventions to reduce pain and inflammation. Chiropractic manipulation may be dangerous since it may promote further spinal cord injury. The anatomy of the spine is quite different in dogs compared to humans. The practice of chiropractic manipulations requires an expert understanding of anatomy; the vast majority of chiropractors receive no veterinary training and few veterinary colleges offer classes in chiropractic therapy. Thus neither chiropractors nor veterinarians consistently possess the appropriate knowledge or skill set to practice chiropractic medicine in dogs. One should also note it is illegal for chiropractors to treat dogs for compensation without supervision by a licensed veterinarian.

Surgical Management:

For patients with marked or progressive neurologic deficits secondary to intervertebral disc disease, surgery is preferred. Certainly surgery offers the best chance for meaningful recovery if an affected dog that cannot walk. Prognosis following surgery depends on the stage of clinical disease. Several surgical procedures may be used to decompress the spinal cord and remove displaced intervertebral disc material, including:

- Hemilaminectomy

- Pediculectomy

- Dorsal laminectomy

- Ventral slot

- Fenestration

What is my pet’s prognosis?

The prognosis for a pet with acute intervertebral disc disease depends on a variety factors. A major factor is a pet’s ability to perceive pain. This is often referred to as deep pain perception (DPP), and a summary of prognoses based on DPP is found below:

| Grade | Non-Surgical Recovery Rate | Surgical Recovery Rate |

| Ambulatory / Partial inability to use limbs | 72.5% | 98.4 |

| Non-ambulatory / partial inability to use limbs | 79.8% | 93% |

| Complete paralysis with intact DPP | 56% | 93% |

| Complete paralysis with no DPP | 22.4% | 61% |

The take-away message about IVDD…

Intervertebral disc disease is a painful and debilitating condition. Intervertebral discs can traumatically rupture, expelling material directly at the spinal cord to cause damage. Affected patients may be managed either with surgery or medical interventions depending the type, severity, and duration of injury. Patients should be evaluated as soon as possible. Consultation with a board-certified veterinary neurologist or surgeon is strongly recommended for any patient with suspected IVDD.

To find a board-certified veterinary neurologist, please visit the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine.

To find a board-certified veterinary surgeon, please visit the American College of Veterinary Surgeons.

To find a board-certified veterinary sports medicine and rehabilitation specialist, please visit the American College of Veterinary Sports Medicine and Rehabilitation.

Wishing you wet-nosed kisses,

CriticalCareDVM