Social media are truly curious phenomena. Opinions abound, including those unsupported by actual fact. We’ve all read them. Last week I read a dangerously inaccurate post regarding canine parvovirus that claimed humans made this potentially deadly disease. This post made my blood boil. Yet rather than perpetually fume, I’ve decided to be proactive. So over the next two weeks, I’ll share some important information about parvovirus in dogs. This week we’ll explore the origin of the virus and how to diagnose it. Happy reading!

Parvovirus – What is it?

Parvoviruses are a group of viruses that belong to the family Parvoviridae. They are classified as single-stranded DNA viruses and are surrounded by a protein coat (called a capsid). They are also quite small; in Latin, parvus means small. These viruses like to infect rapidly dividing cells in their hosts, including those in the intestinal tract, bone marrow, and lymph system.

Scientists isolated the first canine parvovirus called CPV-1 or minute virus of canines (MVC) from dog feces in 1967 in Germany. This virus was relatively innocuous to most dogs, excepting neonates (1-3 weeks of age) in which it caused diarrhea, respiratory problems, and loss of appetite.

In 1976, scientists in Europe isolated another version of canine parvovirus called CPV-2. Veterinarians documented this disease in the United States in 1978. Research suggests this variant is actually the result of 2-3 mutations of the feline parvovirus. Most cat owners know feline parvovirus by its more common names, feline panleukopenia and feline distemper. For those familiar with core feline vaccines, the “P” in the FVRCP vaccine stands for panleukopenia. To complicate matters, CPV-2 subsequently evolved into different variants:

- CPV-2a – isolated in 1979

- CPV-2b – isolated in 1984

- CPV-2c – first detected in Italy in 2000, and diagnosed in the United States in 2006.

Currently, CPV-2c is the most common canine parvovirus variant in the United States. Traditionally, each parvovirus is very species specific. This means the dog parvovirus can’t infect people. But it can affect basically any member of the Canada family, including wolves and foxes. Recently, researchers discovered a mutation in CPV-2c that allows it to infect cats too.

Parvovirus – How do dogs get it?

Canine parvovirus is quite hearty with worldwide distribution. Essentially, canine parvovirus is everywhere. Preventing exposure of puppies to it is nearly impossible. Yet, not every patient exposed to the virus develops clinical signs of disease. Major factors that influence infection are:

- Health of patient’s immune system (including immunization history)

- Virus virulence & load

- Environmental factors

Remember canine parvovirus is everywhere in the environment – dog parks, backyards, floors, etc. Infected dogs also shed the virus in their feces for up to two weeks. As the virus is so robust in the environment, non-immune dogs can become infected months later!

When canine parvovirus was initially isolated, patients both young and old were clinically affected. Yet today we traditionally only document disease in puppies. Why? To understand this, one must have a basic understanding of the immune system. Remember the health of a patient’s immune system influences the occurrence (and severity) of infection. When canine parvovirus infects a dog, the body makes special proteins called antibodies. These antibodies act to neutralize the virus, hopefully preventing infection (or at least lessening the severity of clinical signs). When puppies are born, they are unable to make these protective antibodies. They are 100% unprotected until they ingest their mother’s colostrum, the milk produced during the first 1-2 days of life. Colostrum contains antibodies from the mother. Thus, if the mom is vaccinated against parvovirus, some of her antibodies against this virus will be transferred to her offspring. They will subsequently provide a variable level of protection until these antibodies wear off after 12-16 weeks.

Parvovirus – What does it do in the body?

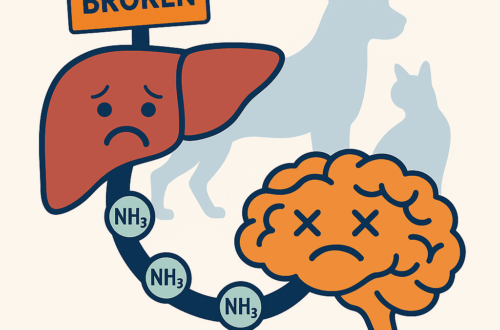

The virus infects dogs through the mouth when they clean themselves or eat food off the ground/floor. Remember it only takes a small amount of virus to infect a dog! When the virus enters the mouth, it immediately travels to an area with rapidly dividing cells. In the mouth, this location is the lymph nodes of the throat where the virus sets up shop and replicates abundantly. After a couple of days, enough virus has been produced to result in its release into the bloodstream. Subsequently, the virus is transported to other areas in the body with rapidly dividing cells, particularly the bone marrow and intestinal tract. Given this pathway, patients typically develop clinical signs of parvovirus after 3-7 days of viral incubation in the body.

Canine parvovirus destroys immature white blood cells in the bone marrow. By doing so, the virus severely incapacitates a patient’s ability to mount a meaningful immune response. In the intestinal tract, a special surface called the villi absorbs nutrients and fluid. These cells turnover rapidly, and must be replaced frequently. Special structures called crypts make new villi cells. Canine parvovirus attacks crypts, leading to the loss of this important absorptive surface. The result? Large volumes of diarrhea that some say has a very distinct odor. Without an intact absorptive barrier, bacteria in the intestinal tract readily gain access to the bloodstream to cause system infection. The severe loss of fluid in diarrhea and subsequent dehydration, as well as blood infection from intestinal bacteria, are the major ways canine parvovirus kills dogs.

Parvovirus – How is it diagnosed?

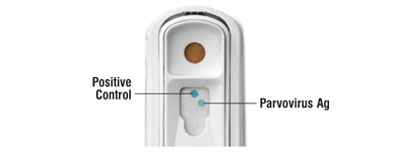

There are many potential causes of diarrhea in puppies. Thus, making an accurate diagnosis of canine parvovirus is important to ensure veterinarians prescribe appropriate therapies. Thankfully, veterinarians have at their disposal some excellent tests to diagnose canine parvovirus. These tests include:

- Fecal ELISA test – ELISA stands for enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. This test is the most common one used. It is performed in hospital, and takes approximately 15 minutes to get results. A limitation of this test is the potential for a false-positive result if a patient has received a live vaccine within two weeks of testing. False-negative results are also possible if the patient is not currently passing virus in its feces or if the virus is thoroughly coated with antibodies, preventing a test reaction.

- Fecal PCR test – PCR stands for polymerase chain reaction, and this assay is relatively new. A veterinarian must submit a sample of feces to a reference laboratory, and thus results may take several days. False-positive results are possible in vaccinated dogs or those passing clinically insignificant amounts of virus in feces.

- Intestinal biopsy – Canine parvovirus causes some classic changes in the intestinal tract that are readily identified via biopsy. However, surgery or minimally-invasive endoscopy to obtain these biopsies is not typically practical because infected patients are quite debilitated, making anesthesia a very risky proposition. Furthermore, safer techniques are available to help make an accurate diagnosis.

Many veterinarians will concurrently evaluate a patient’s white blood cell count to support the veracity of the fecal ELISA test. Remember the canine parvovirus attacks the bone marrow before it strikes the intestinal tract. Doctors expect an infected patient to have a low white blood cell (WBC) count or to ultimately observe a precipitous WBC count drop.

The take-away about the cause and diagnosis of canine parvovirus…

Canine parvovirus is a small virus that is ubiquitously present in the environment. After entering the body, it replicates in various locations with rapidly dividing cells. After incubating in the body for up to a week, dogs develop clinical signs, particularly diarrhea. A fairly accurate in-house fecal test is available to veterinarians, allowing them to institute therapy expeditiously.

To find a board-certified veterinary emergency and critical care specialist, please visit the American College of Veterinary Emergency and Critical Care.

To find a board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialist, please visit the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine.

Wishing you wet-nosed kisses,

cgb