In previous posts I’ve discussed a variety of kidney problems, including chronic kidney disease. This week I wanted to focus on a subcategory of renal ailments – those characterized by excessive loss of protein through the kidneys. This problem is generically called protein losing nephropathy or PLN and is a meaningful health problem in our furry family members. I hope you find this information helpful and shareworthy. Happy reading!

PLN – What is it?

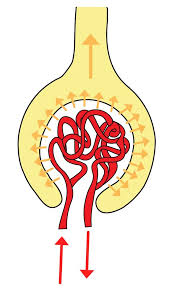

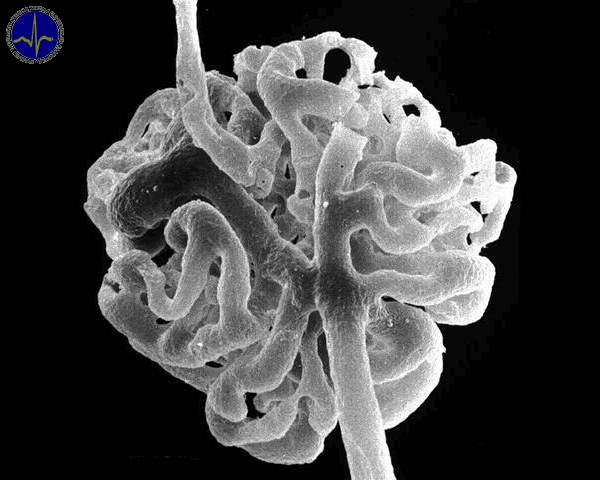

The functional unit of a kidney is called a nephron, and each kidney has approximately one million of them. Each nephron has a glomerulus, which is a cluster of blood vessels and nerve endings surrounding a kidney tubule. Glomeruli are important because they act as a sieve for important molecules. Under normal conditions, large and negatively charged molecules (including proteins!) can’t pass through intact glomeruli.

To understand PLN, one needs to know a little bit about protein in urine in general, a problem called proteinuria. The major causes of proteinuria are classified in terms of their relationship to glomeruli:

- Pre-glomerular – excessive protein delivered to the kidneys

- Glomerular – intrinsic glomerular disease (aka PLN)

- Post-glomerular – kidney tubule damage and lower urinary tract disease

Protein losing nephropathy is excessive loss of protein in the urine due to injury to glomeruli, causing glomerular proteinuria.

PLN – What causes it?

There are three general types of PLNs:

- Glomerulonephritis (GN)

- Glomerulopathy

- Amyloidosis

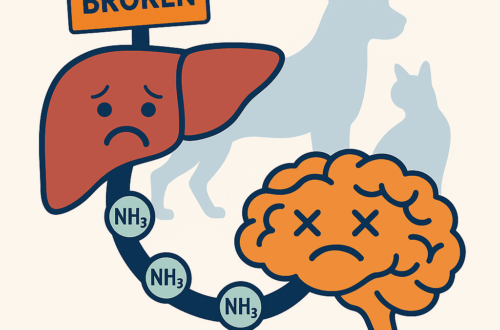

There are many potential causes of GN, particularly Infectious diseases (tick-borne disease, brucellosis, bacterial endocarditis, feline leukemia virus, feline infectious peritonitis), cancers, inflammatory conditions (pancreatitis, polyarthritis, chronic skin disease), and hormone disorders (diabetes mellitus, Cushing’s disease). Unfortunately, often times we aren’t able to definitively determine the cause of GN, and thus the term idiopathic is applied. Chronic skin conditions and cancers are associated with amyloidosis, and certain breeds (Shar Peis, Abbysinians) are over-represented. Similarly, soft-coated Wheaton terriers and English cocker spaniels are over-represented for familial glomerulopathy.

PLN – What does it look like?

The clinical appearance of patients with PLNs varies widely. Some patients have no clinical signs with proteinuria discovered during wellness evaluations. Other patients develop weight loss and lethargy. With marked protein loss, patients develop limb swelling (called edema) and abnormal fluid accumulation in the abdominal cavity (called ascites). Kidney failure is not always present in patients with PLNs, but if it is, affected pets often show increased thirst and/or frequency of urination, as well as decreased (or loss of) appetite, nausea, and vomiting.

PLN – How is it diagnosed?

As there are several types of proteinuria, it is imperative to first determine the type of proteinuria with which a pet is living. To make this differentiation, a veterinarian will thoroughly review a pet’s history, perform a complete physical examination, and evaluate some simple blood and urine tests.

Once glomerular proteinuria is confirmed, then the hunt for the underlying cause begins. As we discussed above, there are several potential causes. Blood, urine, and diagnostic imaging studies (including abdominal sonography) may be recommended. A kidney biopsy may ultimately be needed for a definitive diagnosis. A thorough diagnostic investigation is needed to maximize the likelihood of a meaningfully positive outcome. Families may find it uniquely helpful to partner with a board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialist to develop a logical and cost-effective diagnostic plan.

PLN – How is it treated?

Pets with PLNs need to be treated with a medication(s) that changes pressures inside glomeruli to help reduce the degree of protein leakage into urine. There are two major classes of drugs that help achieve this goal:

- Angiotensin receptor antagonists/blockers (i.e.: telmisartan, losartan, candesartan)

- Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors (i.e.: benazepril, enalapril)

Another main stay of therapy for PLN is feeding a diet with a restricted protein content. There are a wide variety of prescription diets with modified protein content. Pet parents may also wish to collaborate with a board-certified veterinary nutrition specialist to formulate a home-cooked diet for their fur baby.

As mentioned earlier, some PLNs are caused by an inappropriate response by the immune system. These patients benefit from medications that modulate how the immune system responds to various stimuli. Examples of common immunomodulating medications are corticosteroids (i.e.: prednisolone), cyclosporine, mycophenolate, azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, and leflunomide.

A majority of dogs with PLN have high blood pressure, and thus these patients should patients require medication(s) to control their hypertension. Patients with PLN often lose a unique protein called antithrombin in their urine. As a result, these pets are at increased risk for developing abnormal blood clots (called thromboemboli). To help reduce the likelihood of this potentially life-threatening complication, patients should be treated with specific class of medications called anti-thrombotics. Patients with amyloidosis may benefit temporarily from medications like colchicine and dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO), but unfortunately there is no meaningfully effective long-term therapy for this condition. Patients with concurrent kidney failure need additional therapies. Those pets who develop edema may respond to a diuretic medication called spironolactone, and short-term use until edema is controlled is rational.

As you can tell, chronic management of PLN is multi-faceted and can be challenging. The prognosis for patients with PLN is variable. Early and accurate identification coupled with aggressive multimodal therapy has been associated with survival times greater than 1-2 years in those patients without concurrent renal failure. Unfortunately, prognosis is poor in those with meaningful kidney failure with an average survival time of one month. Pet parents may find it helpful to meet with a board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialist to develop the most appropriate treatment plan for their pet.

The take-away message about PLN in dogs and cats…

Protein losing nephropathy or PLN is general category of kidney disease characterized by excessive protein loss in the urine due to damage to the kidneys. There are a variety of potential causes. A thorough diagnostic investigation is essential to accurately diagnose this condition and institute appropriate therapies in a timely manner.

To find a board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialist, please visit the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine.

To find a board-certified veterinary nutrition specialist, please visit the American College of Veterinary Nutrition.

Wishing you wet-nosed kisses,

CriticalCareDVM