Dogs and cats can develop a variety of airway and lung conditions like chronic bronchitis and asthma. Unfortunately, they can also develop a lesser known but debilitating condition called pulmonary fibrosis. This week I wanted to spend some time discussing this lung condition. I hope you find the information interesting and helpful. Happy reading!

Pulmonary Fibrosis – What is it?

Pulmonary Fibrosis – What is it?

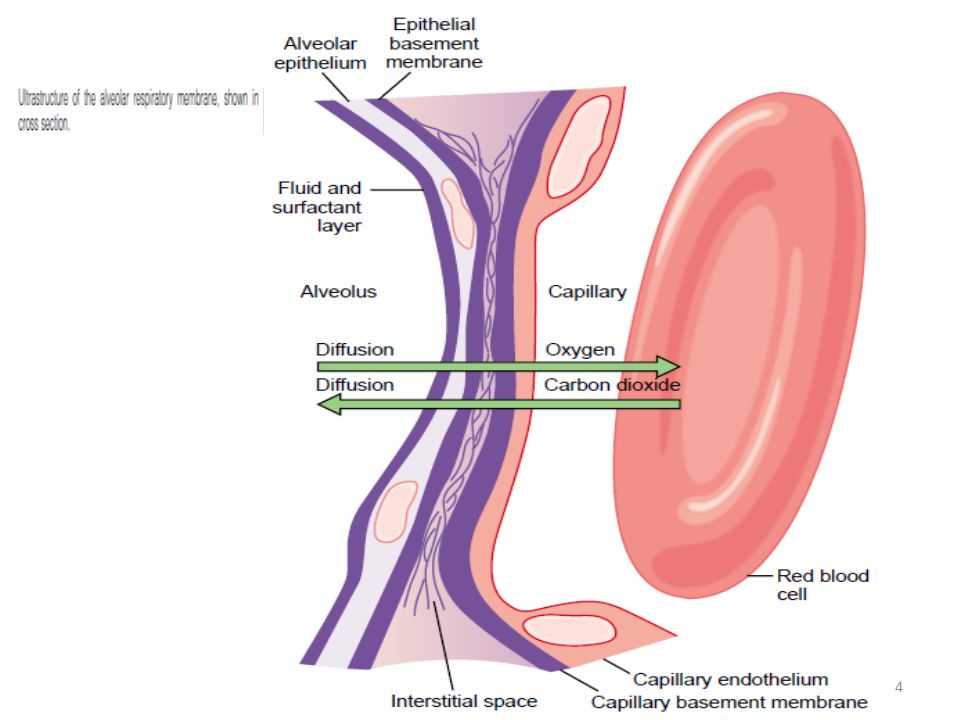

To understand pulmonary fibrosis, you need to first have abasic understanding of how oxygen gets from the lungs to the blood. Air enters the respiratory tract through the nose. It travels through the nasopharynx through the larynx (voice box) and into the trachea (windpipe). From the trachea, air travels through arborizing bronchi and bronchioles until it reaches the alveoli, grape-like clusters of air sacs. It’s here where oxygen and carbon dioxide diffuse across a barrier that is only three cells thick –this barrier is called the respiratory membrane. The three layers are the alveolar epithelium, the interstitial space, and the capillary endothelium. Oxygen moves from alveoli into capillary blood, and carbon dioxide moves from capillary blood to alveoli to be exhaled.

Veterinarians don’t fully understand the exact cause of pulmonary fibrosis. A genetic component is strongly suspected based on multiple studies documenting predisposed breeds and increased gene expression. A current theory suggests scarring or fibrosis of the respiratory membrane develops due to a defective healing process following an insult that damages alveoli. This alveolar damage induces progressive fibrosis. As the respiratory membrane becomes more fibrotic, oxygen and carbon dioxide aren’t able to diffuse efficiently.

Pulmonary Fibrosis – What does it look like?

Pulmonary fibrosis doesn’t have a sex predilection. However, it’s most often documented in middle-aged and geriatric dogs. West Highland white terriers are over-represented for developing this condition. Indeed, pulmonary fibrosis is often called “westie fibrosis.” Pulmonary fibrosis is a chronic and progressive disease; most patients develop clinical signs over several months and often are bright and alert during most times.

Clinical signs often reported by families include:

- Exercise intolerance

- Coughing

- Gagging

- Increased panting

- Rapid breathing

- Difficulty breathing

- Lethargy

- Collapse

- Wheezing

- Cyanosis (blue/purple/grey tint to tongue and gums)

- Reduced appetite

A veterinarian will perform a complete physical examination. They will listen carefully to both the lungs and heart with a stethoscope to listen for abnormal sounds including bilateral inspiratory crackles, wheezes, abnormal heart rhythms, heart murmur, and/or abnormal breathing effort.

Pulmonary Fibrosis – How is it diagnosed?

After performing a complete physical examination, a veterinarian will recommend some non-invasive testing, including:

- Minimum database blood/urine testing to screen for systemic/metabolic conditions that could cause similar clinical signs

- Blood gas analysis to evaluate a patient’s ability to oxygen (breathe in oxygen) and ventilate (breathe out carbon dioxide)

- Pulse oximetry to measure hemoglobin saturation with oxygen in the body – hemoglobin transports oxygen throughout the body

- Diagnostic imaging (i.e.: chest radiographs/x-rays and/or computed tomography) are very important for looking at the airways and lungs

- Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid analysis is a minimally invasive lung test used to help rule out other lung disorders

- Lung biopsy is required to make a definitive diagnosis of pulmonary fibrosis

Pet parents will likely find it invaluable to partner with a board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialist to develop a cost-effective and logical diagnostic plan.

Pulmonary Fibrosis – How is it treated?

To date, we do not have a long-term effective treatment for pulmonary fibrosis. Some may temporarily benefit from anti-inflammatory and airway dilating medications. Anti-fibrotic medications used to slow disease progression in humans have not yet been sufficiently studied in dogs. As the disease progresses, many require chronic oxygen supplementation, necessitating the use of oxygen tents at home. Furthermore, some benefit from anti-cough drugs, as well as medications to reduce pulmonary hypertension. Unfortunately, the long-term prognosis for affected pets is poor with a mean survival time of ~11 months. Anecdotal evidence suggests early diagnosis and subsequent initiation of supportive therapies may prolong survival with some pets surviving 3-4 years.

The take-away message about pulmonary fibrosis in dogs & cats…

Pulmonary fibrosis is an uncommon debilitating lung condition that negatively affects a pet’s ability to breathe comfortably and adequately. A lung biopsy is required for definitive diagnosis. To date there is no specific treatment for pulmonary fibrosis, and treatments are purely supportive in nature.

To find a board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialist, please visit the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine.

Wishing you wet-nosed kisses,

CriticalCareDVM