I’ve written about a lot of different types of cancers that affect our canine friends – lymphoma, mast cell tumors, and hemangiosarcoma to name a few. A couple of weeks ago I evaluated and diagnosed a wonderful dog with a less common cancer called transmissible venereal tumor or TVT. This week I’m sharing information about TVT to raise awareness. Happy reading!

What is transmissible venereal tumor?

Also called Sticker’s sarcoma, TVT is a contagious tumor transmitted between dogs. This disease has also been documented in foxes, coyotes, and wolves. This cancer does not occur in cats. Cancerous cells are most commonly transferred during mating, but they may also be spread through sniffing, biting, and/or licking areas affected by tumor cells.

Transmissible venereal tumor is found most often in tropical (and subtropical) locales with large populations of free-roaming sexually intact dogs. This cancer is endemic in dozens of countries around the globe, as well as parts of the United States.

What does TVT look like?

Transmissible venereal tumor may be diagnosed in dogs of any sex and breed. With that being said, it’s most often diagnosed in adult sexually mature dogs. Cancer cells are usually found in the anatomical regions listed below. Associated clinical signs are parenthesized.

- Genitals (discomfort, licking, discharge)

- Eyes (discharge, eyelid masses, blepharospasm, conjunctivitis, corneal inflammation)

- Nose (sneezing, discharge, difficulty breathing, snoring)

- Skin

- Rectum

- Internal organs

Lesions start as slightly raised red lesions but then progress to become friable masses. They often have a cauliflower-like appearance and are ulcerated and/or hemorrhagic due to excessive licking and/or scratching.

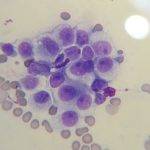

How is TVT diagnosed?

Veterinarians will initially suspect transmissible venereal based on a dog’s thorough history and complete physical examination findings. Fine needle aspiration – the collection of cells with a vaccine-sized needle – is the initial diagnostic test of choice. Collected cells should be evaluated by a board-certified veterinary pathologist; this test is called cytology. Occasionally cytology is not diagnostic, necessitating a surgical biopsy.

Once TVT is definitively diagnosed, some non-invasive tests are recommended to determine the health and function of major organ functions and find out of the cancer has spread. This diagnostic process is called staging, and includes the following blood, urine, and diagnostic imaging tests:

- Complete blood count

- Serum biochemical profile

- Urinalysis

- Diagnostic imaging of the chest and abdomen (usually radiographs/x-rays suffice, but occasionally, abdominal sonography and/or advanced imaging like computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging are recommended)

How is transmissible venereal tumor treated?

Some TVT masses spontaneously regress within three months. Most require intervention, especially if no regression has been noted within nine months. Chemotherapy with a drug called vincristine is the treatment of choice. This drug is given intravenously, and such treatment results in complete tumor regression in up to 95% of patients. Another intravenous chemotherapeutic drug called doxorubicin may be used in those patients who don’t adequately respond to vincristine therapy. Treatment with a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug called piroxicam has been associated with partial regression of TVT, and some board-certified veterinary oncologist recommend oral piroxicam therapy with concurrent intravenous chemotherapy.

Surgery may be recommended for small solitary lesions in surgically accessible sites. Lastly, radiation therapy may be considered for patients with tumors resistant to chemotherapy and/or in certain anatomic locations (e.g.: eye, brain). Pet owners are encouraged to consult with a board-certified veterinary oncologist to determine the most appropriate treatment for their dog.

The take-away message about transmissible venereal tumor in dogs…

Transmissible venereal tumor is a contagious tumor most commonly found in adult sexually mature dogs. Treatment of choice is chemotherapy if the cancer doesn’t spontaneously regress.

To find a board-certified veterinary oncologist, please visit the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine.

Wishing you wet-nosed kisses,

CriticalCareDVM