One of the most common patients seen in veterinary emergency rooms around the world is that of a cat who can’t urinate. These painful critters are frequently called “blocked” cats, and absolutely require immediate veterinary care. This week I wanted to spend some time discussing urethral obstructions in cats, so I hope you find the information helpful. Happy reading!

Urethral Obstruction – What is it?

The urethra is the narrow tube that connects the urinary bladder to the outside world. Urine travels through the urethra from the urinary bladder and out through the penis or vulva. The urethra in the penis is very narrow, and thus uniquely susceptible to obstruction. Urethral obstruction in female cats is rare.

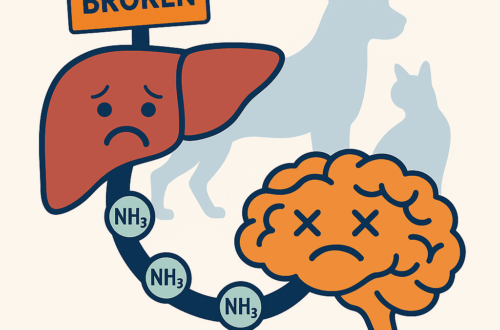

When the urethra is blocked, the urinary bladder distends markedly and rapidly. The pressure inside the urinary bladder rises precipitously. Under normal circumstances, this increased pressure would generate signals to the brain that subsequently tells a patient to urinate. When urination isn’t possible because of a urethral obstruction, the pressure in the urinary bladder is transmitted to other structures, including the kidneys. Without prompt relief of the obstruction, the urinary bladder may rupture and the kidneys may be irreparably damaged.

Urethral obstruction is most commonly caused by an accumulation of inflammatory cells, mucus, and crystals; stones called calculi may also cause obstruction. Inflammatory material, mucus, and crystals form a plug that obstructs the urethra, preventing an affected cat from urinating. The reason for the accumulation of inflammatory cells, mucus, and crystals is not fully understood. Some documented risk factors for urethral obstruction in cats are:

- Stress

- Being kept indoors

- Eating only dry food / kibble

- Multi-cat households

- Nervous / aggressive / fearful temperament

Less common causes of urethral obstruction are trauma and cancer. Urethral obstructions are true emergencies, and pets should be evaluated by a veterinarian as soon as possible. When cats can’t urinate, metabolic waste products accumulate in their blood. Affected cats may be quite distressed and profoundly painful.

Urethral Obstruction – How is it diagnosed?

Affected cats are typically young to middle aged. Clinical signs may be very mild or quite severe, and may include:

- Frequent attempts to urinate

- Minimal-to-no urine production (pollakiuria)

- Straining to urinate (called stranguria)

- Vocalizing while attempting to urinate

- Urinating outside of the litter box

- Restlessness

- Blood in the urine (hematuria)

- Vomiting

- Lethargy

- Reduced (or loss of) appetite

Many pet parents mistake cats straining to urinate for cats who are constipated. This can be a dangerous error!

Many pet parents mistake cats straining to urinate for cats who are constipated. This can be a dangerous error!

I recommend veterinarians evaluate as soon as possible cats who appear to be straining to urinate or defecate.

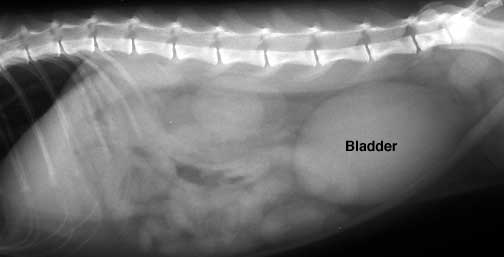

Physical examination of cats with urethral obstructions identifies very large, firm, and painful urinary bladders. Severely affected patients may be weak, lethargic, and poorly responsive because of rapidly accumulating blood levels of toxic metabolic waste products. Body temperatures may be low and heart rates may be inappropriately reduced as well.

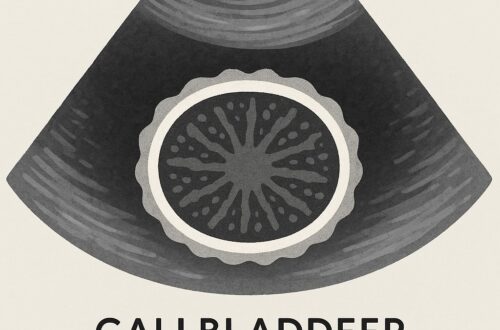

Veterinarians will perform some non-invasive blood and urine tests in cats with urethral obstructions. This testing is essential to evaluate kidney functions, measure important electrolyte levels (i.e.: potassium), and evaluate the amount of acids accumulating in the blood. Analyzing urine is critical to identify crystals and possible concurrent bacterial urinary tract infection. The doctor may also obtain radiographs (x-rays) or perform sonography of the urinary bladder to look for stones (calculi).

Urethral Obstruction – How is it treated?

As I mentioned earlier, cats with urethral obstructions require emergency veterinary treatment. The vast majority of our feline friends require sedation or anesthesia; severely affected cats who are poorly responsive may not require any drugs to relieve their urethral obstruction. A veterinarian will use a special catheter and fluid to relieve a urethral obstruction. Once the obstruction has been cleared, the doctor will lavage or flush the urinary bladder in an attempt to remove any debris that may have accumulated that could cause re-obstruction. Provision of appropriate pain medication is of paramount importance, as patients should be as comfortable as possible. Tearing of the urethra while trying to relief an obstruction is possible but seemingly uncommon.

Cats who can’t urinate often have marked elevations of blood kidney values. The severity of these derangements depends chiefly on the duration of obstruction. After relieving their obstructions, most cats require intensive intravenous fluid therapy to help rid the bodies of toxic metabolic waste products. Blood potassium levels are often elevated. This abnormality may cause life-threatening heart rhythms. As such, patients with elevated blood potassium levels (called hyperkalemia) need medications to protect the heart (i.e.: calcium gluconate) and to reduce blood potassium levels (i.e.: insulin, terbutaline). Some cats accumulate too many acids in their blood. Depending on response to intravenous fluid therapy, some require a medication (i.e.: sodium bicarbonate) to neutralize the acids.

A urinary catheter is typically left in place connected to a closed collection system for monitoring purposes and to allow swelling in the urethral to subside. A “blocked” cat often produce extraordinary volumes of urine after relieving an obstruction. This phenomenon is called a post-obstruction diuresis, and is the reason cats benefit from hospitalization after clearing urethral obstructions. Without appropriate monitoring and intravenous fluid therapy, cats with post-obstructive diuresis rapidly become dehydrated and decompensate.

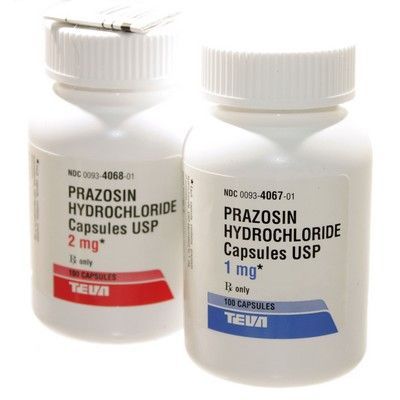

The urethra frequently spasms after an obstruction is cleared. Some drugs (i.e.: prazosin, diazepam) help to reduce or eliminate these spasms. When the pressure in the urinary bladder gets too high or is elevated for a prolonged period of time because of a urethral obstruction, the contracting muscle of the urinary bladder (called the detrusor) is damaged. When the detrusor muscle is injured, the urinary bladder can’t empty normally even when there isn’t an obstruction! Keeping the urinary bladder small by keeping a urinary catheter in place for several days and by administering a specific medication (i.e.: bethanecol) helps the detrusor repair itself.

Upon discharge from the hospital, the veterinarian will discuss various strategies to help reduce the likelihood of recurrence of a urethral obstruction. Some recommendations may include dietary modification and methods to reduce stress. Partnering with a board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialist can be instrumental in developing logical long-term treatment plan.

Cats who have had previous urethral obstructions, as well as those with stones causing an obstruction, typically need surgery. The necessary surgery is performed after patients are metabolically stable from the kidney and electrolytes derangements commonly associated with urethral obstructions. Repeat offenders benefit from a surgery called a perineal urethrostomy. Cats with stones need to have them removed, typically through a urinary bladder surgery. Pet parents may find it helpful to partner with a board-certified veterinary surgeon who is expertly trained to perform these surgical procedures.

The take-away message about urethral obstruction in cats…

A urethral obstruction in a cat is a potentially life-threatening emergency. A patient should be evaluated by a veterinarian as soon as possible. The doctor will work to efficiently relieve the obstruction and identify concurrent problems that are the result of the urethral obstruction. With prompt relief and appropriate post-obstruction care, patients can make a complete recovery.

To find a board-certified veterinary surgeon, please visit the American College of Veterinary Surgeons.

To find a board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialist, please visit the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine.

Wishing you wet-nosed kisses,

cgb