Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are relatively common in companion animals. Given the frequency of UTI diagnosis, the International Society for Companion Animal Infectious Disease (ISCAID) developed guidelines for the diagnosis and management of urinary tract infection. One should not confuse guidelines with “standards of care”, as the former are simply meant to aid a veterinarian’s clinical decision-making. Treatment contrary to established guidelines might, indeed, be appropriate. Nevertheless guidelines can help veterinarians manage the vast majority of patients with UTIs.

It’s usually just an infection

The bodies of dogs and cats have multiple natural defense mechanisms to prevent urinary tract infections. Yet occasionally these defenses fail or are overwhelmed. When this happens, UTIs happen. Bacteria commonly enter the urinary tract from the outside environment, often from a pet’s own feces. The bacteria travel through the urethra, the tube that connects the outside world to the urinary bladder. When an otherwise healthy pet develops a UTI but has no history of recurrence or relapse, we use the term simple uncomplicated UTI.

Dogs and cats with UTIs show a variety of clinical signs, including:

- Frequent urination of small volumes of urine (called pollakiuria)

- Urgency to urinate

- Difficulty urinating (called dysuria)

- Excessive licking of vulva or penis

- Blood in urine (called hematuria)

- Discharge from the vagina

- Incontinence

- Cloudy and/or fetid/smelly urine

- Depression / lethargy

- Reduced (or loss of) appetite

Your pet’s veterinarian will ask you a lot of questions about your pet’s clinical signs, and it is important you answer all of them completely. The doctor should also perform a thorough physical examination, as well as a complete urinalysis, including evaluation for red blood cells, white blood cells, and bacteria. While a urine culture is ideal and always provides useful information, it isn’t absolutely necessary for patients with simple uncomplicated UTIs. Amoxicillin and trimethroprim-sulfa are often prescribed first-line antibiotics, but broader spectrum drugs may be indicated. Treatment duration is often 7-10 days, but research is ongoing to identify the optimum treatment duration.

But it’s not always just an infection

If treatment of a bacterial UTI fails or if the infection recurs after seemingly appropriate treatment, veterinarians should consider all the factors that could have resulted in such an outcome. These factors result in what we call complicated UTIs, and possible reasons for treatment failure or infection recurrence include:

- Inappropriate use of an antibiotic (e.g.: incorrect dose, inadequate duration, poor family compliance with administration)

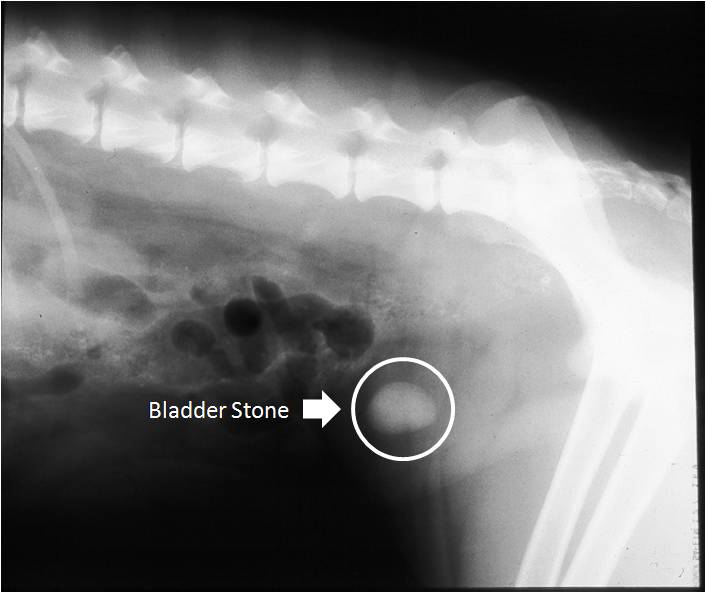

- A nidus within the urinary tract (e.g.: urinary bladder stone, tumor, kidney infection/pyelonephritis, prostatic diseases)

- An anatomical abnormality (e.g.: recessed/hooded vulva, obesity) – see video below of a dog with a markedly recessed vulva

- A concurrent metabolic disease (e.g.: chronic kidney disease, diabetes mellitus, hyperadrenocorticism/Cushing’s disease)

- Patients receiving medication(s) that suppress the immune system

A culture of the urine should always be performed for patients with complicated UTIs to identify the specific bacterium that is causing a urinary tract infection. While awaiting culture results, a veterinarian will initially prescribe a specific antibiotic similar to those prescribed for simple uncomplicated infections, but treatment may need to be modified based on both urine culture results and a patient’s response to therapy. Complicated UTIs can truly be just that – complicated to both diagnose and treat. For that reason, it is often invaluable to partner with a board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialist to help develop the most efficient and cost-effective diagnostic and therapeutic plans.

And sometimes it isn’t even an infection

Believe it or not, the presence of bacteria in urine (termed bacteriuria) does not necessarily mean a pet is living with a UTI. To have an infection implies having disease. In both human and veterinary patients, patients may have bacteria in their urine with no evidence of disease – none of the clinical signs mentioned earlier like urgency to urinate, blood or white blood cells in the urine, and pain with urination. This phenomenon is called subclinical bacteriuria. Patient populations frequently documented to be living with subclinical bacteriuria are dogs and cats with diabetes mellitus. There is no evidence treatment with an antibiotic reduces the risk of a UTI. Thus in an effort to minimize the development of antibiotic resistance, treatment of subclinical bacteriuria is not recommended. Consultation with a board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialist can be uniquely beneficial if you or your family veterinarian believe your pet has subclinical bacteriuria.

The take-away message about urinary tract infections…

Urinary tract infections in dogs and cats are common medical conditions. While the vast majority are simple uncomplicated ones, UTIs can become complicated due to a variety of factors. In such situations, partnering with a board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialist can be invaluable to efficiently identify the cause of your pet’s UTI and develop an effective treatment plan.

To find a board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialist, please visit the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine.

To find a board-certified veterinary emergency and critical care specialist, please visit the American College of Veterinary Emergency and Critical Care.

Wishing you wet-nosed kisses,

cgb