This week’s post was written in response to a request for more information from a dedicated follower. Uveitis or inflammation of the uveal tract of the eye is frequently diagnosed in both dogs and cats. Thus, it’s important for pet parents to have a working knowledge of this problem. So, I hope you find the information helpful. Happy reading!

Uveitis – What is it?

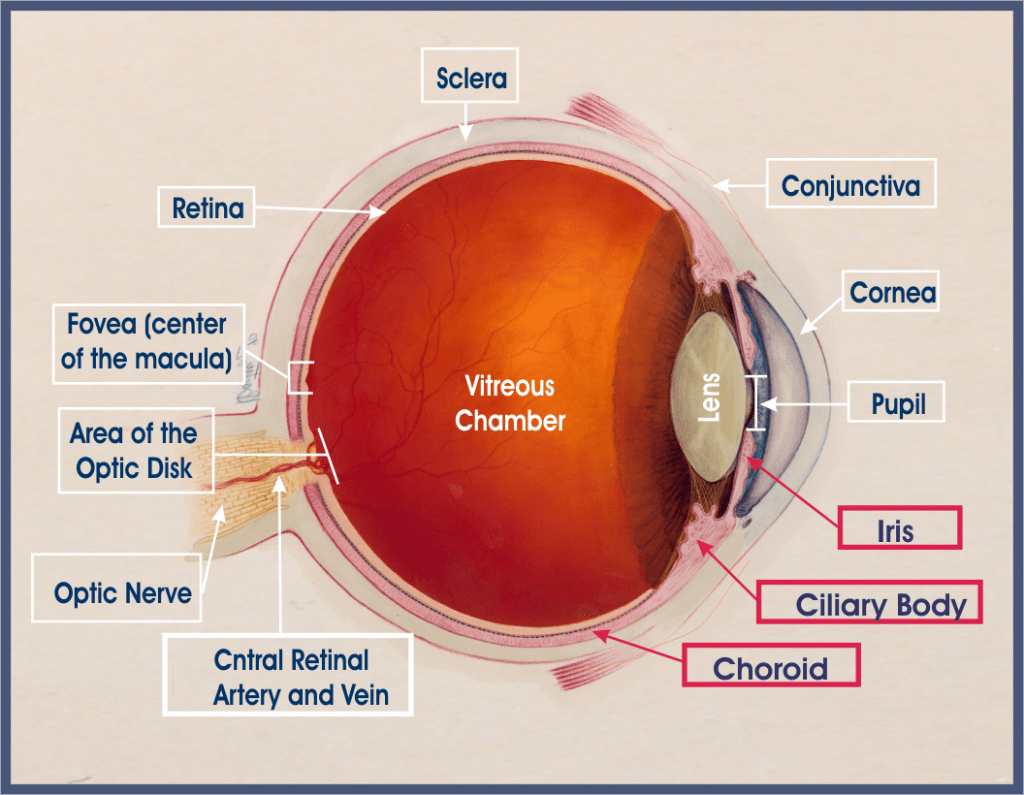

The eye has three basic layers:

- Fibrous (outer) layer – composed of the cornea and sclera

- Vascular (middle) layer – the uvea

- Neuroectodermal (inner) layer – composed of the retina and optic nerve

This post is focused on the vascular or middle layer called the uvea. The uvea is further divided into three parts:

- Iris – the colorful part of the eye that controls the amount of light entering the eye by changing the size of the pupil

- Ciliary body

- Choroid

The iris and the ciliary body form the anterior uvea while the choroid is commonly called the posterior uvea. Uveitis simply means inflammation of the uvea. Each part of the uvea is continuous with the other, meaning inflammation typically affects more than one part of the uveal tract. Common terms used to describe uveal inflammation are:

- Anterior uveitis – inflammation of the iris and ciliary body

- Posterior uveitis – inflammation of the choroid and ciliary body

- Panuveitis – inflammation of all parts of the uvea

Uveitis – What does it look like?

There many clinical signs associated with uveitis, most notably

- Photophobia – sensitivity to light

- Blepharospasm – involuntary closure of the eyelids

- Epiphora – excessive tearing

- Pain – often manifests as depression and reduced (or lack of) appetite

Other eye changes that may be seen with uveitis are discoloration of the cornea, constriction of the pupil (called miosis), deformation of the pupil, discoloration of the iris, and evidence of inflammation in part of the eye called the anterior chamber (space between the cornea and the iris). Eyes with uveitis often appear redder than normal due to inflammation.

Uveitis – How is it diagnosed?

The veterinarian will obtain an exhaustive patient history. They will also perform a complete physical examination, including a thorough ophthalmic evaluation. Every patient with a “red eye” like that typically seen in patients with uveitis should have three important non-invasive tests performed – they are so important they are often called the “Big 3.” These tests are:

- Schirmer tear test – to assess ability to produce adequate volume of tears

- Fluorescein dye test – to check for damage to the cornea

- Tonometry – to check the pressure inside each eye (called intraocular pressure)

Patients with uveitis often have low intraocular pressures. The veterinarian should also use some special instruments to look at different parts of the eye, including the anterior chamber and the retina. The use of a slit lamp (aka biomicroscopy) and ophthalmoscope to completely evaluate the eye is profoundly important. Many primary care doctors don’t have these instruments and will recommend partnering with a board-certified veterinary ophthalmologist.

Based on a patient’s history and examination findings, the uveitis is classified (i.e.: anterior vs. posterior vs. pan) and ultimately categorized as one of the following:

- Infectious organisms (i.e. bacterial, fungi, algae, protozoa, viruses, etc.)

- Immune-mediated

- Toxin-induced

- Traumatic

- Associated with systemic disease

- Unknown etiology

To achieve accurate categorization, the veterinarian may need to perform some non-invasive tests (i.e.: blood/urine assays, diagnostic imaging, etc.) to help identify the underlying cause.

Uveitis – How is it treated?

Treatment depends on the underlying cause and the severity of inflammation. Accurately identifying and effectively treating the proper etiologic cause of uveitis is of paramount important for successful management of this condition. The veterinarian may inject and/or prescribe topical and systemic anti-inflammatory medications to control the intense inflammation in the eye. A class of medication called a cycloplegic should be prescribed to help reduce pain, dilate the pupil, and present damage to the iris. Systemic pain medications may also be temporarily needed. Occasionally, medications to modulate how the immune system reacts are needed. Pet parents are encouraged to collaborate with a board-certified veterinary ophthalmologist to develop the most effective treatment plan.

The take-away message about uveitis in dogs and cats…

Uveitis or inflammation of the uvea is a relatively frequent eye problem documented in dogs and cats. There is a myriad of potential causes, and prompt diagnosis and intervention are needed to save and preserve a patient’s vision.

Wishing you wet-nosed kisses,

CriticalCareDVM