Dogs and cats unfortunately develop masses frequently. Whether these masses are associated with the skin or are growing inside a body cavity, they can cause serious and potentially life-threatening problems for pets. Thus their removal is often imperative to maximize the best possible outcome for affected animals.

Mass Removal Point #1: “See Something, Do Something”

If you have been following this blog, you are likely familiar with the concept of “see something, do something.” This is a mantra penned by board-certified veterinary cancer specialist, Dr. Sue Ettinger Heuter (DrSueCancerVet), which tells us any skin mass that has been present for more than one month or is larger than the size of a pea should be evaluated/tested by a veterinarian. If a skin mass is determined to be cancerous, surgical removal before it has an opportunity to grow too large and/or invade surrounding tissue maximizes the chance for a cure.

To read more about “see something, do something” and testing skin masses, please click here.

Mass Removal Point #2: Pre-Operative Testing

Most masses, whether they are skin masses or growing in a body cavity, require surgery to remove. To perform surgery, heavy sedation or general anesthesia is required. Occasionally local anesthesia can be utilized to safely remove small skin masses, but this is not very common.

Sedatives and anesthetic agents cause a variety of physiologic changes in the body, and proper organ function is imperative to metabolize them properly. Thus just as your own doctor requires for you, your pet, too, should have some simple blood/urine tests performed prior to sedation or anesthesia, including:

Complete blood count – a non-invasive blood test that tells about red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets (cells that help form a blood clot)

Serum biochemical profile – a non-invasive blood test that tells about electrolytes (sodium, potassium, etc.), as well as liver and kidney function

Urinalysis – a non-invasive assessment of urine that provides information about kidney function and reveals potential evidence of urinary bladder inflammation and/or infection

Coagulation testing – a non-invasive blood test that tells us if a pet can form a proper blood clot

In my experience, the above-listed recommended tests are not always performed or are performed incompletely.

Don’t forget the urine!

Evaluation of urine is absolutely essential for proper assessment of kidney function, and the analyzed urine sample should be collected first thing in the morning so it is maximally concentrated.

Some primary care veterinarians only merely suggest pre-surgical testing be performed, and allow pet parents to decline this important pre-anesthetic screening. These doctors unquestionably actually recommend testing, but have a policy that allows declination so they will still be able to perform the surgery even if testing is declined. After all if a veterinarian tells a pet parent that s/he won’t perform the needed surgery without appropriate pre-anesthetic testing, that veterinarian could lose the client’s business.

Allowing a family to decline pre-anesthetic testing may be a smart business decision, but it can’t be considered best medical practice!

Would you decline your doctor’s recommendation for pre-surgical blood/urine testing for your own surgery? I fathom many of you would readily say, “No!” I ardently argue you should answer similarly for your pet!

Mass Removal Point #3: Surgery

Understandably surgery to remove a skin mass is entirely different than surgery to remove a mass from inside the chest or abdominal cavity. Therefore a detailed discussion of surgery is beyond the scope of this blog post. However I do want pet parents to know about the minimally recommended monitoring modalities for a heavily sedated or anesthetized patient in the operating room.

Vital signs: Body temperature, heart/pulse rate, and respiratory/breathing rate should be measured at least every five minutes while a patient is sedated or anesthetized.

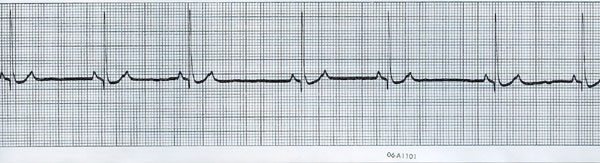

Electrocardiography (ECG or EKG) – a non-invasive test that screens for abnormal electrical activity in the heart

Blood pressure (BP) – With each heartbeat, blood is pumped into arteries; blood pressure is the force of the blood pushing against the walls of the arteries. Blood pressure is highest when the heart beats (called systolic pressure) and is lowest between heartbeats (called diastolic pressure).

To read more about blood pressure monitoring in dogs and cats, click here.

Pulse oximetry – This is a non-invasive test that provides information about the oxygen saturation of hemoglobin. Red blood cells contain hemoglobin that binds oxygen to be carried to all of the tissues of the body, and we want hemoglobin to be as saturated as possible!

End-tidal Capnography (ETCO2) – This is a non-invasive monitoring tool that measures the concentration of carbon dioxide in a patient’s expired breath.

I strongly encourage pet parents to ensure their pet will be properly monitored in the operating room during surgery. If appropriate monitoring is not available, one may find peace of mind to have surgery performed at a veterinary specialty hospital where this level of monitoring is the standard of care.

Mass Removal Point #4: Post-Operative Considerations

The degree of post-operative care a patient requires varies depending on a myriad of factors, most notably the site of surgery, invasiveness of the removed mass, and concurrent health conditions of the pet. But there are three post-operative issues about which I believe every pet parent should know:

Pain management: Any time an incision is made, pain is created. If pain is created, pain control is mandatory! There is absolutely no excuse for a recovering surgical patient not to receive analgesia, and pain management should ideally be initiated before pain (i.e.: surgery) is induced. In many patients, the use of more than one pain medication (called multimodal analgesia) is quite advantageous, allowing more effective pain control with lower drug dosages. Yet for some reason, a (thankfully) diminishing number of family veterinarians actually allow pet parents to decline post-operative pain medication for recovering surgical patients. In my opinion, this is unequivocally inappropriate and should not be allowed.

Biopsy results: Any mass removed from the body should be evaluated by a board-certified veterinary pathologist to determine if it is benign or malignant. Every single graduate of a college/school of veterinary medicine is taught the same mantra:

If it is worth taking off or taking out, it is worth finding out what it is!

What does this mean? It means if a veterinarian believes a mass should be removed, s/he also believes the nature of the mass (i.e.: cancerous or benign) should be definitively determined. Yet just as for pre-surgical blood/urine testing and post-operative pain medication, some primary care veterinarians allow pet parents to decline figuring out what a mass is. If you had a mass removed from your body, wouldn’t you want/need to know what it is? Would you allow your own surgeon to throw the removed mass in the garbage? Of course you wouldn’t! Why would you consider such an action for your pet’s removed mass? You may be asking, “Why do some primary care doctors allow such a practice?” The answer is often quite simple, and it is not because they don’t know or understand the importance of the biopsy information. Rather these well-intentioned colleagues don’t want to say “no” because pet parents could become upset and take their business elsewhere.

Don’t ignore the doctor’s instructions: Following the post-operative home care instructions of your pet’s veterinarian should be a common sense action. Yet for many pet parents, they perceive these instructions as suggestions rather than the recommendations they are. Furthermore when complications arise (because they didn’t follow the specific home care instructions provided to them), they become frustrated with, angry at, and even violent toward the veterinary team. Home care instructions from veterinarians are not suggestions. They are very specific recommendations, and should be followed to the T!

The Take-Away Messages About Mass Removal

It is quite common for a dog or cat to need a mass removed from its body at some point in its life. Prior to surgery, specific blood/urine tests are recommended to ensure vital organ function is adequate to minimize the risks of sedation or anesthesia. Any mass removed from the body should be evaluated by a board-certified veterinary pathologist to determine exactly what it is! Surgical patients should receive pain medication to ensure they are as comfortable as possible, and pet parents should follow all home care instructions provided to them.

To find a board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialist, please visit the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine.

To find a board-certified veterinary emergency and critical care specialist, please visit the American College of Veterinary Emergency and Critical Care.

To find a board-certified veterinary surgeon, please visit the American College of Veterinary Surgeons.

Wishing you wet-nosed kisses,

cgb