In a previous post, I reviewed a cancer in dogs called lymphoma. You can find that information here. Unfortunately, lymphoma also commonly affects our feline friends. So, this week I’ve dedicated some time to spreading news about lymphoma in cats. I hope you find it helpful. Happy reading!

Lymphoma – What is it?

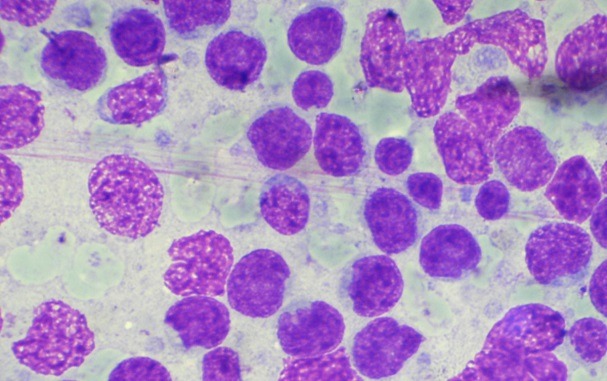

Lymphoma – commonly abbreviated as LSA – is a cancer of a type of white blood cell called the lymphocyte. Lymphocytes are part of the blood (hematopoietic) system. Blood-derived cancers account for ~30% of all cancers in cats. Lymphoma is exceedingly commonly, comprising 50-90% of blood-derived cancers in our feline friends. Lymphoma can affect various and multiple sites throughout the body, most notably:

- Gastrointestinal tract – most common

- Kidneys

- Central nervous system

- Nasal passages

- Mediastinum

- Skin

- Peripheral lymph nodes

- Larynx (voice box)

- Trachea (windpipe)

There are two main forms of gastrointestinal lymphoma:

- Enteropathy-associated T-cell LSA Type I – this form is also called high-grade, large cell, or lymphoblastic lymphoma. There is a subtype called large granular LSA that is very aggressive.

- Enteropathy-associated T-cell LSA Type II – this form is the most common, and is typically called low-grade, small cell, or indolent lymphoma

Lymphoma – What causes it?

Any breed of cat may develop lymphoma. Siamese cats appear to be over-represented. Male cats seem to be affected more often. The typical age of diagnosis is approximately 11 years of age. However, cats with mediastinal lymphoma are often younger with a median age of 2-4 years. Several risk factors have been identified:

- Gastrointestinal inflammation – some researchers have postulated there is a connection between uncontrolled inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and the development of LSA

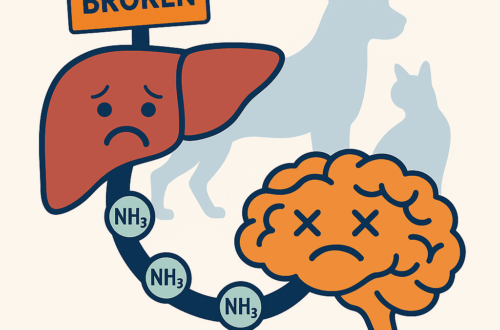

- Feline leukemia virus (FeLV) – may lead directly to LSA

- Feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) – patients with FIV have a more than 5-fold increase in a diagnosis of LSA

- Immune system suppression – cats receiving immune system suppressing medications after kidney transplants are predisposed to developing LSA

Lymphoma – What does it look like?

The clinical signs associated with lymphoma depend on the site of involvement:

- Gastrointestinal tract – reduced (or loss of) appetite, vomiting, diarrhea, weight loss, dehydration

- Kidneys – weight loss, reduced (or loss of) appetite, vomiting, increased thirst, increased frequency of urination

- Central nervous system – abnormal behavior, seizures, abnormal eye movements, weakness, paralysis

- Nasal passages – congestion, sneezing, bloody nose (called epistaxis), facial deformity, eye discharge

- Mediastinum – increased respiratory rate, respiratory distress, weight loss, reduced (or loss of) appetite, Horner’s syndrome

- Skin – slow growing, reddened, plaque-like lesions typically on the head and/or face

- Peripheral lymph nodes – enlargement of single or multiple lymph nodes

- Larynx (voice box) & trachea (windpipe) – increased breathing noises, gagging, change to meow

Lymphoma – How is it diagnosed?

A veterinarian will obtain a complete patient history and perform a thorough physical examination. Some non-invasive blood and urine testing (e.g.: complete blood count, biochemical profile, and urinalysis) should be performed. Additional testing is based on the site(s) of involvement, and may include:

- Radiographs (x-rays) of the chest and/or abdomen

- Chest and/or abdominal sonography

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain

- Computed tomography (CT scan) and rhinoscopy of the nasal passages

- Gastrointestinal biopsies

- Cytology +/- biopsy of enlarged lymph nodes

- Immunohistochemical staining

Pet parents are strongly encouraged to consult with a board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialist or cancer specialist to develop a logical and cost-effective diagnostic plan.

Lymphoma – How is it treated?

Most forms of lymphoma in cats are treated with chemotherapy. However, some forms do benefit from surgical intervention. Others may improve with radiation therapy. Feline parents are strongly encouraged to partner with a board-certified veterinary cancer specialist or internal medicine specialist to determine the best course of treatment for their fur babies.

The prognosis for pets living with lymphoma is quite variable and dependent upon the three major factors:

- Location of the cancer

- Type of therapy

- Response to therapy

Below I’ve listed some information about response rates and median survival times for specific anatomic locations:

- Gastrointestinal: Patients with Type I LSA treated with chemotherapy have a 50-75% response rate with a median survival time of 6-8 months. Approximately 20% will survive 1-2 years. The large granular subtype if very aggressive and unfortunately carries a very poor prognosis with a median survival time of less than 60 days. Patients with Type II lymphoma treated with chemotherapy have an ~75% response rate with median survival times of more than two years.

- Mediastinal: Most cats respond very well to chemotherapy (~80% response rate) and have a median survival time of 9-12 months. Cats concurrently living with FeLV have much poorer prognoses with reported survival times of approximately 3 months.

- Nasal: Patients treated with radiation therapy +/- chemotherapy respond very well to treatment with a >90% response rate and survival times up to 2-3 years.

- Kidney: LSA affecting the kidneys carries a poor prognosis with median survival times of ~3 months.

- Central Nervous System: This form of LSA carries a poor prognosis with a reported survival time of 70 days.

- Skin: To date, reliable data regarding response rate and median survival time is not available.

- Larynx/Trachea: Although this form of LSA tends to respond well to chemotherapy, the median survival time is typically less than 6 months

The take-away message about lymphoma in cats…

Lymphoma is a very common blood-borne cancer in cats. It affects various anatomic locations throughout the body, most commonly the gastrointestinal tract. Once diagnosed, treatment with chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and/or surgery often leads to an improvement in quality of life – at least temporarily. Prognosis is largely dependent on the site of the cancer, the type of therapy provided, and whether a patient responds to prescribed interventions.

To find a board-certified veterinary cancer specialist, please visit the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine.

To find a board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialist, please visit the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine.

Wishing you wet-nosed kisses,

CriticalCareDVM