In recent posts I wrote about two of the major cells types in blood – red blood cells and platelets. Specifically I reviewed causes of low red blood cells and low platelets. This week I introduce the last major cell type in blood – white blood cells – and discuss reasons why their population can increase.

White blood cells – what are they?

White blood cells, also called leukocytes, are cells that defend the body against various diseases, including infectious organisms (i.e.: bacteria, virus, fungi, protozoa, etc.) and cancer. An elevated white blood cell count (called leukocytosis) can happen for a number of reasons, including:

- Increased production to fight an infection

- Reaction to a drug that increases production

- A bone marrow disorder that causes increased production

- A disorder of the immune system that increases production

White blood cells or WBCs are made in the bone marrow, are released into circulation, and ultimately travel to various tissues to do their respective jobs. White cells are highly differentiated for various specialized functions, and on the basis of their appearance under a microscope, they are grouped into three major classes, each of which has different functions:

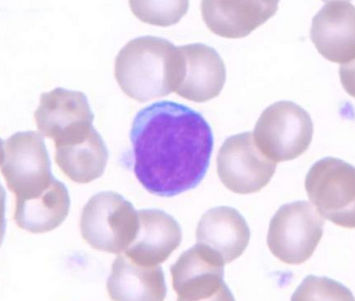

- Lymphocytes

- Granulocytes

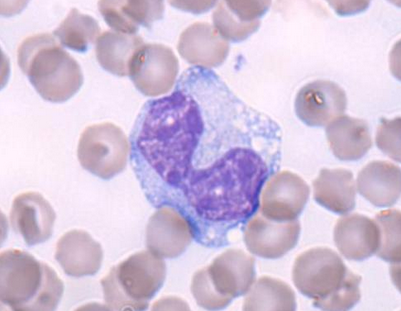

- Monocytes

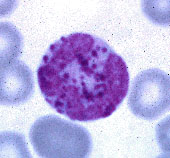

There are two types of lymphocytes – B and T cells. B-lymphocytes secrete antibodies, special proteins that bind to foreign organisms in the body to help destroy them. Think of antibodies as special blood soldiers charged with assassinating foreign invaders. T-lymphocytes recognize cells infected by viruses or infiltrated by cancer and subsequently try to destroy them; they also help B-lymphocytes make antibodies.

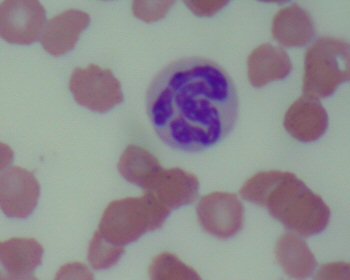

Granulocytes are the most common type of white blood cells in circulation. These cells contain many granules filled with potent chemicals involved in immune responses. They help the body get rid of certain types of infectious organisms, and are also involved in inflammatory processes and allergic reactions. On the basis of how their granules take up dye in the laboratory, granulocytes are subdivided into three types:

- Neutrophils

- Eosinophils

- Basophils

Neutrophils are typically the first type of white blood to arrive at sites of infection where they engulf infectious organisms in an attempt to destroy them (a process called phagocytosis). Click here to watch a neutrophil capture bacteria. Eosinophils and basophils arrive on the scene later, secreting various chemicals that induce allergic responses, help destroy parasites, and/or modulate inflammatory responses.

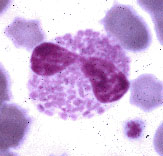

Monocytes travel from blood vessels to sites of infection to become macrophages that scavenge that phagocytosed organisms and cleanup of cellular debris. Some macrophages also aid T-lymphocytes in their immunologic responsibilities.

White blood cells – how are they measured?

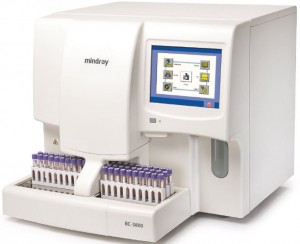

Measuring WBCs is relatively straightforward. A small sample of blood is collected for a non-invasive test called a complete blood count (CBC). A CBC allows a veterinarian to obtain a comprehensive evaluation of blood, as it measures WBCs, as well as RBCs, blood clot-forming cells called platelets. Complete blood counts are performed on machines called hematology analyzers found either at reference veterinary laboratories or in hospitals. There are advantages and potential limitations to performing tests in a veterinary hospital compared to a reference veterinary laboratory. To learn more about this, click here.

A vital component of a CBC is a microscopic examination of blood. No hematology analyzer is perfect, and thus direct visualization of blood cells is crucial to making an accurate diagnosis. Despite this fact and in my experience, this recommended component is often not performed in primary care veterinary practices. Two most commonly cited reasons from primary care doctors for omitting a blood film evaluation are lack of confidence performing a blood film assessment and lack of time to perform the evaluation. In contrast, veterinary reference laboratories are not allowed to omit this step! If veterinary reference laboratories can’t omit peripheral blood film evaluations, then veterinarians performing CBCs in their in-house laboratories can’t omit them either!

The take-away message about elevated white blood cells…

Pet parents often believe their pet needs an antibiotic if their fur baby’s WBC count is elevated. However this is not always true!

An elevated white blood cell count does not always mean there is an infection.

Having an elevated white blood cell count is not necessarily justification for prescribing an antibiotic. Indeed giving a pet an antibiotic without confirming there is actually an infection can be dangerous, potentially promoting antibiotic resistance. Therefore it is very important for a veterinarian to perform a thorough diagnostic investigation to determine the definitive cause of a white blood cell elevation. Consultation with a board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialist can be invaluable for helping develop an efficient and cost-effective diagnostic plan.

To find a board-certified veterinary emergency and critical care specialist, please visit the American College of Veterinary Emergency and Critical Care.

To find a board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialist, please visit the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine.

Wishing you wet-nosed kisses,

cgb