The urinary tract of dogs is comprised of two kidneys, two ureters (tubes that connect the kidneys to the urinary bladder), the urinary bladder, prostate gland (male dogs only), and the urethra (tube that connects the urinary bladder to the outside world). The urinary bladder is the most common site of cancer in the urinary tract. This week I discuss the potential causes, diagnosis, and treatment for urinary bladder cancer in dogs.

Urinary Bladder Cancer – What causes it?

The most common cancer of the urinary bladder in dogs is called transitional cell carcinoma (also called TCC and urothelial carcinoma). This tumor arises from cells lining the inside of the urinary bladder (called transitional epithelial cells), but can invade the deeper layers of the urinary bladder. Transitional cell carcinoma can also spread to regional lymph nodes and other organs like the liver and lungs.

The definitive cause of TCC in dogs is typically not known, and is generally considered to arise from a combination of genetic predisposition and environmental factors. Certain dog breeds are over-represented for developing TCC, including:

- Scottish Terriers

- Shetland Sheepdogs

- Beagles

- West Highland White Terriers

- Wire Hair Fox Terriers

Scottish Terriers have an 18-20 fold higher risk of developing TCC compared to the general dog population, while the other breeds listed above have a 3-5 fold higher risk.

Early clinical studies documented an apparent risk for developing TCC with exposure to pesticides and insecticides. This association was also specifically documented in Scottish Terriers who were exposed to lawns or gardens treated with herbicides and/or insecticides. Exposed dogs were seven times more likely to develop transitional cell carcinoma, resulting in a recommendation to restrict Scottish Terriers and other at-risk breeds from lawns treated with herbicides and pesticides.

Although the most common cause of TCC in humans in smoking, a definitive relationship between secondhand smoke and the development of TCC in dogs is not yet known. A drug called cyclophosphamide has also been associated with the development of TCC in dogs.

Urinary Bladder Cancer – How is it diagnosed?

Affected dogs commonly have a variety of clinical signs, most notably:

- Blood in urine (called hematuria)

- Pain during urination (called dysuria)

- Straining to urinate (called stranguria)

- Frequently urinating only small volumes of urine (called pollakiuria)

- A continual feeling of needing to defecate (called tenesmus)

The clinical signs are not specific for urinary bladder cancer, and more common conditions like urinary tract infections often have identical manifestations.

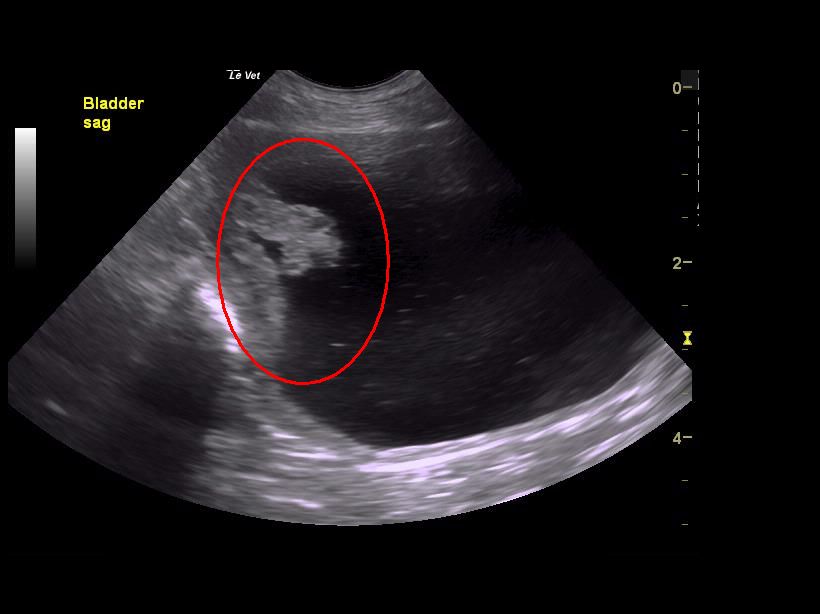

Some dogs will have a mass in or irregular feeling to their urethra and/or prostate palpable via rectal examination. Uncommonly patients may have bone pain or firm swellings of some leg bones secondary to metastatic disease (spread of cancer) or hypertrophic osteopathy, respectively. Abdominal sonography allows a veterinarian to readily identify a mass within the urinary bladder, but ultimately a diagnosis of TCC requires obtaining a biopsy.

Unlike in humans, currently there is no blood or urine test that can 100% accurately diagnose urinary bladder cancer in dogs. Researchers are actively attempting to find proteins in blood (called biomarkers) that will prove diagnostic in dogs. Biopsies from the urinary bladder are typically obtained via either surgery or cystoscopy, a minimally invasive procedure using a specialized fiberoptic camera. In the video below, a veterinarian performs cystoscopy in a dog with TCC located in urinary bladder and extending into the urethra (one can see the tumor starting at 0:54).

After a patient has been diagnosed with TCC, some minimally invasive tests should ideally be performed to determine how affected by the cancer the rest of the body is. This testing is called tumor staging, and involves obtaining chest radiographs/x-rays and abdominal radiographs/x-rays (or performing abdominal sonography).

Urinary Bladder Cancer – How is it treated?

For urinary bladder tumors that have not spread to other organs, surgical removal is ideally performed. However location of the tumor within the urinary bladder is very important. Some areas of the urinary bladder (e.g.: trigone/neck of the urinary bladder; urethra) are simply not amenable to surgery. Picture the urinary bladder like a balloon. The longer yet thinner area of the balloon represents the urethra. The area where the balloon starts to widen is called the trigone or neck; important structures like the ureters insert in this location. Traditional surgery in the trigone and urethra are not feasible.

After surgery (or in patients for whom surgery is not viable), drug treatment is recommended. To date there are several protocols have been used to treat dogs living with TCC, particularly:

- Treatment with a non-steroid anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID): Several NSAIDs have been documented to have some anti-tumor activity. Piroxicam is, perhaps, the NSAID that has been studied most. The reported median survival time for dogs treated with this drug is 195 days.

- Treatment with an NSAID and mitoxantrone: When an NSAID is combined with the intravenous chemotherapy drug called mioxantrone, an additional survival benefit is observed. A remission rate of 35% has been documented, and average survival rates are 250-300 days.

- Treatment with vinblastine: Vinblastine is an injectable chemotherapeutic drug that been used effectively to improve quality of life in patients living with TCC.

Other drugs have been explored for the treatment of urinary bladder transitional cell carcinoma in dogs, including gemcitabine, carboplatin, and metronomic therapy. I recommend pet parents consult with a board-certified veterinary cancer specialist to help design the most appropriate treatment plan for an affected patient. In areas where a board-certified veterinary cancer specialist is not available, consultation with a board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialist is recommended.

Palliative therapies for transitional cell carcinoma have also been investigated, including:

- Placement of a permanent cystotomy tube: A permanent cystotomy tube is a tube placed in the urinary bladder that communicates with the outside world; such a tube may be placed when an animal is no longer able to urinate because his/her urinary bladder tumor is blocking the proper flow of urine. Pet parents have to routinely open the tube to allow the urine to drain from the urinary bladder. Thus use of a permanent cystotomy tube requires exquisite at-home care to ensure a pet doesn’t disturb/damage the tube and to help reduce the likelihood of infection.

- Radiation therapy: Although several protocols for providing radiation therapy to affected patients have been described, such intervention is not commonly performed due to limited availability and potentially serious side effects.

- Laser therapy: Affected pets with urinary outflow obstruction may temporarily benefit from laser ablation of a urethral or trigonal urinary mass. Specialized training is required to perform such procedures. Laser ablation can be repeated when a tumor recurs locally.

- Urethral stent placement: A stent is hollow structure that expands within the urethra to hold that tube open after it has been occluded by a tumor. Although temporary relief can result, side effects include urinary incontinence and migration of the stent.

Palliative therapies may add 3-4 months of good quality life when incorporated with standard chemotherapy, and some dogs have survived more than 1.5 years.

The take-away message about urinary bladder cancer in dogs…

Urinary bladder tumors are relatively uncommon, but when present, can significantly and negatively affects a patient’s quality of life. The most common urinary bladder tumor is transitional cell carcinoma. Early diagnosis and therapeutic intervention are instrumental for maximizing successful outcomes. Pet parents are strongly encouraged to partner with a board-certified veterinary cancer specialist to develop the best treatment plans for their fur babies.

To find a board-certified veterinary cancer specialist, please visit the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine.

To find a board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialist, please visit the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine.

Wishing you wet-nosed kisses,

cgb