Cats and dogs can develop gastrointestinal ulceration just like you and me. For this week’s post, I’m sharing more information about this relatively common condition to raise awareness. I hope you find the information insightful. Happy reading!

What causes gastrointestinal ulceration?

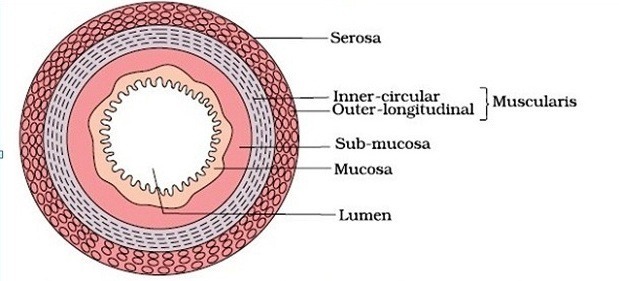

The wall of the gastrointestinal tract has four layers. From inside to out, they are the mucosa, submucosa, muscularis, and serosa. Ulcers occur when the innermost layer (mucosa) is damaged. Damage may occur anywhere in the gastrointestinal tract, but the last part of the esophagus, the stomach, and the duodenum (the first part of the small intestine) are most commonly affected.

There are many potential causes of gastrointestinal ulceration in cats and dogs, most notably:

- Adverse drug reactions (e.g.: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs / NSAIDs, steroids)

- Cancers (e.g.: mast cell tumors)

- Toxins

- Foreign objects

- Stress

- Shock

- Kidney disease

- Liver diseases

- Gastric dilatation-volvulus (aka “bloat”)

What does it look like?

When the mucosa of the gastrointestinal tract becomes ulcerated, it bleeds. When bleeding occurs in the esophagus and the stomach, patients frequently vomit because blood readily induces nausea. The vomitus often looks like coffee grounds or crushed Oreo cookies because of a chemical reaction with and partial digestion of blood by stomach acid. Occasionally, vomitus contains fresh red streaks mixed with food and/or saliva, and these streaks represent fresh and undigested blood.

When bleeding occurs in the esophagus, stomach, and small intestine, the blood may pass through the gastrointestinal tract just as food does. Various digestive enzymes metabolize the blood, causing it to ultimately form black, tar-like feces. This is called melena and represents digested blood in bowel movements. When bleeding occurs in the colon, feces contain fresh red streaks of blood on their surface or feces may look like thick gelatinous raspberry jam. This is called hematochezia and represents fresh bleeding mixed with mucus.

Cats and dogs who bleed due to gastrointestinal ulceration may have minimal clinical signs. Sometimes the only evidence of ulceration is visualization of blood in vomitus and/or feces. Bleeding into the stomach and small intestine readily induces nausea. Accordingly, some animals vomit, lose weight, have reduced appetites, and/or drool excessively. Other pets may be presented in shock because they’ve bled a lot and/or their ulcers have perforated.

How is gastrointestinal ulceration diagnosed?

Diagnosing gastrointestinal ulceration is indirectly based on visualizing fresh and/or digested blood in vomitus and/or feces. Determining the cause of the ulceration, however, can be challenging. Veterinarians will review your pet’s entire medical history and will perform a complete physical examination. Based on this information, subsequent testing may be recommended, including:

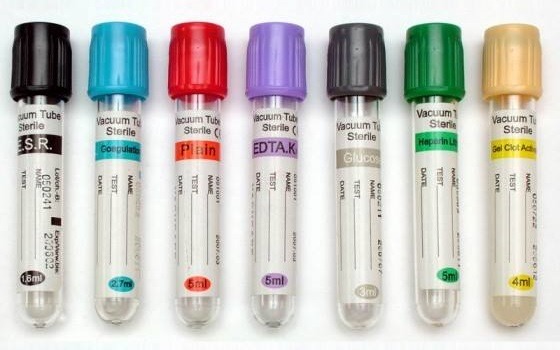

- Complete blood count

- Serum biochemical profile

- Urinalysis

- Fecal/stool examination

- Abdominal diagnostic imaging (e.g.: radiography/x-rays, ultrasonography)

- Clotting tests

- Infectious disease tests (depending on your geographic location)

- Testing for certain hormone disorders (e.g.: hypoadrenocorticism/Addison’s disease)

- Endoscopy (using a fibre-optic camera to look inside the gastrointestinal tract and to obtain biopsies, if indicated)

Pet owners may find it helpful to collaborate with a board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialist to develop a logical diagnostic plan.

How is it treated?

It is imperative to identify and effectively treat the underlying cause of a patient’s gastrointestinal ulceration. For example, if a patient is receiving a class of medication known to cause ulceration, the medication should be discontinued. Sometimes, immediate intervention is needed. A patient with a perforated ulcer requires emergency surgery.

In addition to definitive therapy to address the underlying cause of a pet’s gastrointestinal ulceration, supportive therapies are indicated too. These interventions include:

- Stomach acid suppressors (reduce the potency of stomach acid to reduce further injury caused by stomach acid) – examples include omeprazole, famotidine, ranitidine, and cimetidine

- Sucralfate (acts as a liquid bandage for the mucosa)

- Misoprostol (helps to repair the mucosa)

- Anti-nausea medications

- Pain medications

- Temporary dietary modification

- Promotility medications (drugs that promote improved movement of food through the gastrointestinal tract)

- Appetite stimulants

The take-away message about GI ulceration in cats & dogs…

Gastrointestinal ulceration is a relatively common issue in cats and dogs. There are a variety of potential causes, necessitating a thorough diagnostic investigation. Therapies are aimed at identifying the underlying cause(s) and supporting/protecting the lining of the GI tract.

To find a board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialist, please visit the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine.

Wishing you wet-nosed kisses,

CriticalCareDVM